“Three two one, one two three. Hang a Nazi from a tree.” That’s how Jacob the Horse choose to open “Bad New Religion,” their new single we’re premiering today and one of the clearest mission statements in this whole rollout. As Aviv Rubinstien puts it, it’s not an accident that the first thing that arrived was the first thing you hear: “This basically never happens, but the first line that came to me is the first line of the song… which is also why that doesn’t match any other cadence of the rest of the song.”

Rubinstien frames it as a song that refuses the comfortable version of “political punk,” where anger gets filed down into something palatable. “Speaking of ‘show me your fangs,’ I was trying to write a song that didn’t have any hope in it whatsoever, because that’s not how I’m feeling,” he says. “I was trying to not give myself, or anyone else, any sort of false hope of unity. So, ‘show me your fangs’ is like chaos. It’s that everyone needs to remind themselves that they still have teeth in this fight, and to start biting and scratching and kicking. If we’re all going to die, at least we can take some of them with us.”

That internal motor—rage, then a second look in the mirror—comes up a lot in how the band talks about the material. Josh Fleury lays out the band’s self-mythology bluntly: “Aviv is the rage. Rick is the tension, and I attempt to be the humor. The guys don’t agree.” Mark Desrosiers doesn’t really fight that reading, he just shrugs at the state of things: “Pretty accurate. I mean, what else can you do but laugh at this point?” And Rubinstien admits the swing between fury and self-heckling is basically the writing process: “It starts out as all rage, and then after I write my angry journal entry, I’ll go back and take a look at myself. Half of the absurdism is what’s going on in the world right now. And the other half is me looking at myself and writing angry poems in my diary, and being like, ‘this is going to change things!’ And so it’s totally self-deprecating in that sense. I don’t know, it’s mostly just fucking angry.”

Rick Chapman remembers the moment the abstract became very practical. “I remember rehearsing the song without words, and then Aviv wrote the lyrics and came to practice and said, ‘Guys, this is going to end us up on a list.’” Desrosiers’ answer: “Pretty accurate.”

Not “political punk” as a costume – more like a nervous system

The band’s references aren’t thrown in as a mood-board. They’re basically a timeline of how each member learned that guitars can be used like a siren.

Rubinstien says the title is an intentional lift: “I mean, the song’s called ‘Bad New Religion,’ so it’s an homage, also theft, of Bad Religion, which was my first political punk band when I was 15 or so. You can’t be punk without being political and you can’t make art. All art is political. After Bad Religion, I got into a little bit of Propaghandi and Fugazi, but mostly my north star is Bad Religion.”

Chapman’s entry point was the Bush-era version of the same sickness: “My foray into political punk was NOFX, and the album The War on Errorism, which came out during the Bush administration. It’s astounding how you listen to those songs now and it’s the exact same situation we’re in now, if not worse. The meaning of those lyrics haven’t changed in the 21 years since that came out.”

Desrosiers goes from the local to the structural: “My political punk bands were Op Ivy which became Rancid, which is a little bit less political, but they still were. Then I went backwards and got really into The Clash, like most people. The Clash isn’t just an interesting band because they’re political, because the personal is political for them. A lot of their songs are vignettes from the perspective of the working class or a third party.”

And Fleury lands on a record a lot of people treat like a cultural artifact rather than a still-functioning warning label: “A highly influential political album for me was American Idiot. I remember that album coming out when I was just starting high school. I didn’t initially understand the message and themes behind it until I made my way through high school and into college. I was like, ‘Oh shit. That’s what they meant?’ Now, 20 years after: Why the fuck is it’s still relevant today?”

That sense of repetition—history looping, but louder—also shows up in how they compare “Bad New Religion” to earlier attempts at protest music. Desrosiers draws the line back to the first Trump era: “We wrote an angry punk song after the 2016 election, which was a little more straightforward, a rousing ‘let’s go get them guys,’ And then here we are ten years later and it’s like the same fucking shit.”

View this post on Instagram

“Bad New Religion” is a livewire inner monologue

Desrosiers describes the song less like a statement and more like a brain refusing to settle: “It’s rapidly switching between thoughts that are very dark and then, ‘no, I’m better than this.’ ‘No, I’m not better than this.’ ‘What if I can’t be better than that?’ ‘What if being better than that is the problem?’ I’ve always seen it as a completely scattered internal monologue.”

Chapman keys in on the domestic-surreal detail of it—apocalypse happening while you’re still doing laundry: “I find myself singing, ‘Soon there will be blood and fire and panic in the streets daily. Just doing my normal household chores.’ The line ‘show me your fangs’ feels like a battle cry.”

Rubinstien’s own explanation of the politics stays pointed and local, not abstract. “There are literal Nazis in the streets of America,” he says. “They’re pushing Trumpism down our throat like that old-time religion. Los Angeles is a really diverse city, and it’s one of the frontlines of Trump’s culture war against the people of the United States.”

He also insists the “outrage music is outdated” line is a tell, not a critique: “I think that if you claim that outrage music doesn’t matter, you’re part of the problem. and there’s a reason that you’re trying to discourage people from speaking– from yelling– their opinion in song.” Desrosiers answers in his own language: “Right. You gotta get the poison out. Sometimes you have to put it in a song.”

The saxophone choice wasn’t a novelty—more like a weaponized grin

“Bad New Religion” also has saxophone on it—credited to Walt Young—and the band talks about it like it’s part of the song’s personality, not decoration. Chapman explains where that came from and why it had to be the right person: “Walt Young is my best friend from high school. We’ve known each other since we were eleven years old. He was the bass player in several bands of mine in high school. And then we went to college. I went to film school. He went to jazz performance school. He has his masters in music education. We wanted to add something more to the song, and the idea of a ‘dick-ripping ’80s sax’ was pitched. We wanted a big saxophone in a similar vein to Jeff Rosenstock, and I was like, ‘I’ve got the guy!’”

Rubinstien uses that moment to spell out how Jacob the Horse actually functions day-to-day: “This speaks to how we write songs. One of us will have an idea, varied in how fully formed it is. Then we’ll all mutate it based on where our instincts say it should go. Most of the time we’re all in alignment. Sometimes we’re not and we’ll talk it through. For this one, I think it was pretty seamless where we all had this angry energy. It was about ironing out all the different pieces that we wanted to include in this one song.” Chapman keeps it simple: “It really came together. It was a full group effort.” Rubinstien adds one more detail that sounds small, but says a lot about authorship inside the band: “Josh and I also co-wrote a different song on the record. And at this point, I cannot remember which lines are from him and which lines are from me.”

Family history isn’t backstory here—it’s part of the alarm system

A big chunk of Rubinstien’s writing on this record is tied to inherited fear that stops being metaphor when you look around. “When you have a real life boogeyman that tried to kill your grandparents, it’s the worst that humanity’s ever been, codified,” he says. “Humanity’s been really fucking bad at several times, but all the books and the movies and the whatever else is like, ‘It doesn’t get worse than Nazis.’ And now they’re just back. My family trauma has sort of programmed me to be really sensitive to stuff like this when it happens. And it’s happening all the time now. It’s really aggravating.”

He also describes the band’s physicality as part of staying functional: “Playing music, especially this music, is half therapy and half aerobic exercise because we’re all running around. We’re all sweating our asses off. Both things are really healthy for my mental state.”

The other members tie their own families into the same contemporary pressure, but from different angles. Chapman talks about assimilation and the cost of it in one breath: “I am a quarter Latino on my mom’s side, and I’d say nearly everyone in her family voted for Trump and supports what’s happening and sees no issue with ICE. And when you try to tell them, ‘hey, they’d take you in a heartbeat if you looked a certain way.’ They’re like, ‘oh no, I’m fine.’ My grandmother was born in Texas right on the Mexican border. She moved to Detroit and grew up with the mindset of, ‘We’re American. We don’t celebrate any of our old culture. We’re going to speak English. We’re going to learn the culture.’ My mom and all my uncles on her side, none of them speak Spanish. My siblings and I don’t speak Spanish. We know very little about our heritage because it’s been completely whitewashed by ’50s Americana. It’s terrible.”

Fleury brings up his mother and says the quiet part out loud without pretending the paperwork solves the mood of the room: “My mom’s an immigrant, originally from Taiwan. She’s been a citizen for decades now, so hopefully there’s nothing to worry about.” Rubinstien answers immediately: “We hope.” Fleury again: “Yeah, we hope.”

He keeps going, into the everyday dread and the family context that makes it sharper: “I always get a terrible feeling in my stomach thinking there are people that are our neighbors who’d see my mom and be like, ‘Get the fuck out of here.’ I feel awful for all the immigrant families who are being torn apart. My dad was an immigration lawyer in New York City in the ’80s, and helped people who were in the process of obtaining their green card and going to immigration court. We’d hear the stories of what the process was and like, the state of things back then compared to what it is now. My head goes spinning sometimes.”

Desrosiers ties his own family’s activism to the exhaustion of repeating fights that should’ve been settled decades ago: “My dad is one of nine, so he has a bunch of sisters and they’re all super incredible. They spent their whole youth and adulthood fighting for equal rights and women being accepted as leaders; women leading from the front about bodily autonomy and rights for abortion, all that. We’ve just gone back to like the fucking ’50s. We just start from fucking scratch. They’re in their ’70s and they’re still fighting the same fights that they were in when they were 18.”

View this post on Instagram

The album context: At Least It’s Almost Over, and why it sounds like this

The single is one part of a bigger record that’s explicitly defined as disillusionment and escalation. Rubinstien calls it out in a line that’s basically the thesis of why “Dead by 45” isn’t enough anymore: “This entire record is me looking back at our song ‘Dead By 45’ and being like, ‘You thought we were going to protest our way out of this? You fucking idiot!’”

He’s equally blunt about what kind of record he thinks it is: “This is a spiteful, angry, depressed record with a purpose. At this point, I’m surviving and living the rest of my life out of spite. The best case scenario is that we find people who also connect with the record, that we’re speaking to them by externalizing the things that they’re already thinking. And worst case scenario? We get thrown in prison or killed by our own government. I don’t know how this all ends for our country. Nowhere is it written that America gets a happy ending.”

He also describes the broader feeling behind the album without trying to polish it: “It feels like they’re leaving us to the wolves,” he says, “and the wolves are these bad people with bad intentions. It feels like the world is ending. People are betraying us as a community. I can barely express the anger and disappointment I feel at having to live in the dumbest timeline.”

There’s also a deliberate contrast between earlier work and this one, in terms of harmony, mood, and what the band wanted to emphasize. “By design, College Party Mixtape was more of a power-pop record with punk leanings,” Rubinstien says. “It was a little bit more positive, a little bit more hopeful, even though it’s still dealing with some of the same kind of anxiety issues that are just living inside me. They’re all major key songs. Then, on At Least It’s Almost Over, we decided to go super riff heavy. Our art was maturing, and I was getting way more radicalized around COVID, Trump, Black Lives Matter and then Trump again. I still like power pop and Fountains of Wayne and stuff, but I found this political-punk muscle that I was eager to flex.”

A lot of At Least It’s Almost Over is described through cinematic and horror language—Russ Meyer nods, cartoon violence, Satan jokes, big riff architecture—and the band insists it wasn’t a calculated genre pivot. “I don’t think that that is calculated,” Rubinstien says. “I think that this is who we are. I don’t think we set out to make a horror punk record or a record that sounds like a ’70s exploitation film.”

Desrosiers admits the original plan was almost embarrassingly different: “We had this idea of what this record was going to be before the election. We were going to write a dad rock record. Something like an Aerosmith or AC/DC record. All these big dad-rock riffs. Then this is what came out when we actually sat down to start writing with everything that was going on.”

Rubinstien traces the Satan angle to classic rock’s theatrical nerdiness—and makes a specific distinction about where “Bad New Religion” sits on the album: “I think that’s where the Satanic humor comes from. All of those bands like Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, Black Sabbath, whoever else, are full of absolute nerds. And yet they’re singing about Satan and Lord of the Rings. I think it’s part of the satanic humor. But, ‘Bad New Religion’ is unique. It’s the only time we mention the devil or Satan on the record as a negative. We say the ‘devil exists not from Scripture or myth, but the guy fucking with trans kids.’ We’re not talking about the same guy in any of our other songs. The guy that we’re talking about in this song sucks.” Chapman agrees on what “devil” means here: “Yeah, I think it’s the societal idea of evil and the devil.”

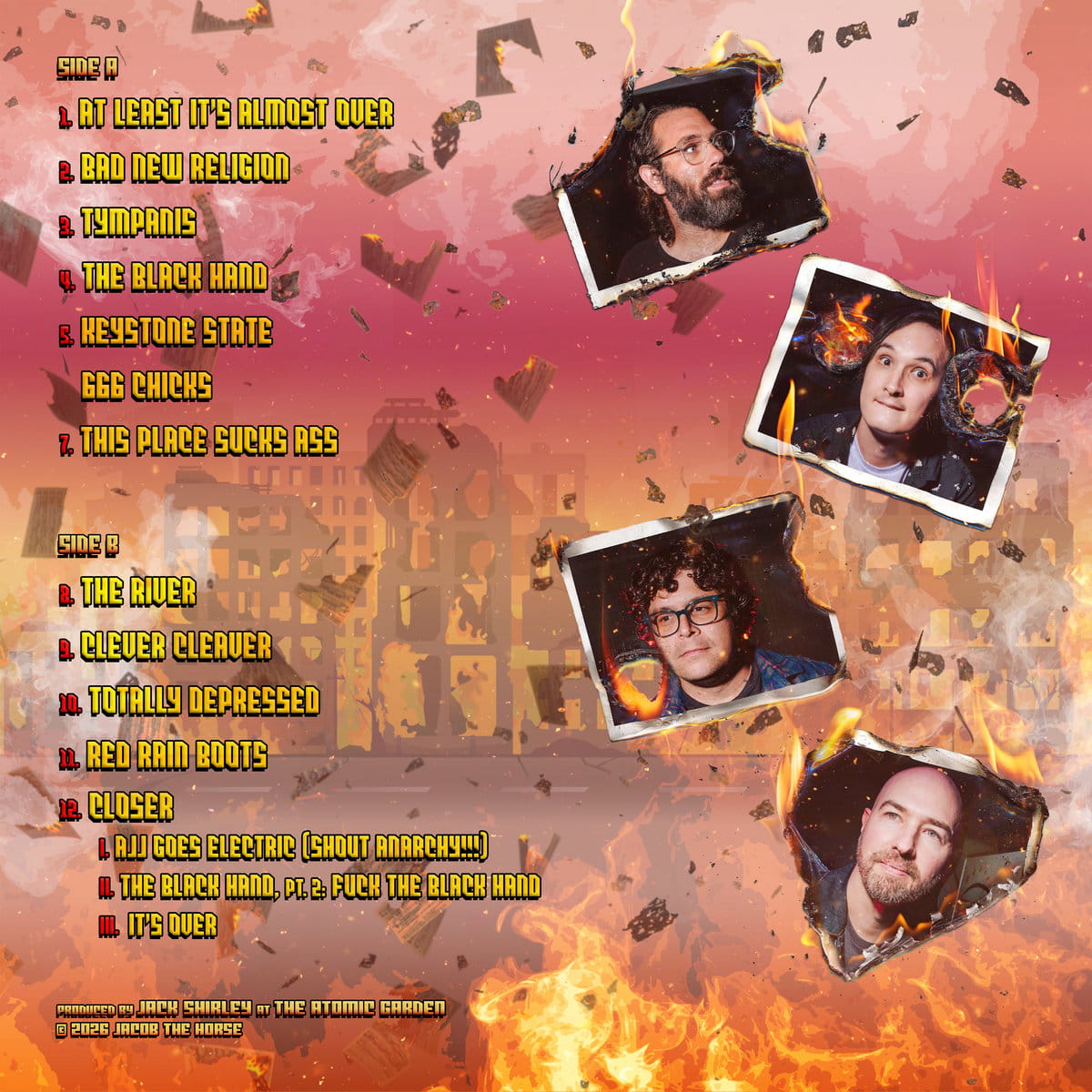

The album art is equally direct in its imagery. The cover is credited to animator and illustrator Jesse James Dean (Bob’s Burgers, Little Demon, Paradise PD, HarmonQuest, Archer, Squidbillies, Aqua Teen Hunger Force). The band’s only note was to “have a giant creature wreaking havoc on a city,” and they pushed the gore further by swapping a chalice for a corpse.

Recording “live,” and angry enough to break the gear

At Least It’s Almost Over was produced by Jack Shirley and recorded at The Atomic Garden in Oakland, with additional engineering & string arrangement by Josh Fleury. Rubinstien talks about getting there like it was equal parts fandom and curiosity: “We had the real honor of recording at the Atomic Garden, which is in Oakland. It’s run by and owned by Jack Shirley. Jack is the best. We basically cold emailed him when we were finishing our last album, because we really liked the work that he did with Jeff Rosenstock and Joyce Manor. The more we dug into Jack, the more we found like, ‘oh, my God, this guy’s the real deal. What does he want to do with us?’”

He also notes the studio’s name has a specific resonance for them: “The Atomic Garden is named after a Bad Religion song, sort of. I’d let Jack tell the story, but it is the name of a Bad Religion song. So we felt like it was the proper alignment for this type of song, this type of place.” The process matters just as much as the badge: “Jack has an amazing process where you don’t play to a click track and you all play in the same room with no headphones. You’re just a human being playing music, as opposed to some other studios which are very isolated. It feels like more of a group effort to me when we get to do that.”

Desrosiers underlines what that means in practice on the final takes: “The final recording has no overdubs for drums, bass, rhythm, and lead guitar. It’s all of us playing live. Maybe we punched a note here or there, but I don’t even know if we did that on this song. It’s not like we took take-three of the drums and take-one of the guitar.”

Rubinstien tells one studio story that sounds funny until you realize it’s literally about trying to capture anger as energy: “This was the song where Rick put his stick through two different drum heads. It was the first song of the day on one of our recording days, and Rick hit the drum so hard that he dented the snare drum. And then Jack’s like, ‘oh, well, I’ll get you a new snare. And this is a ’70s snare and it’s going to sound great. You guys love 70s punk!’ Then, like two snare drum hits in, dented again. He’s like, ‘okay, well, I have one more snare. And if you break that one, we’re done for the day.’ Luckily, Rick didn’t break that one. But that gives you the sense of how angry we are and how we wanted to get the song as energetic as possible.”

Track-by-track

The record opens with the swirling, psychedelic, instrumental title track “At Least It’s Almost Over,” described as “a big breath before a long scream,” with background audio from Night of the Living Dead and orchestral themes that return later.

Then comes “Bad New Religion,” framed by the band as an “angry indie-punk anthem” that pushes past posting and passive coping. In Rubinstien’s words: “It’s delusional to think that anyone can save us in a way that won’t involve a city burning down.”

“Tympanis” gets described as punk colliding with desert rock, with Rubinstien singing lines like “She clutches to her rosary / And carves her name into my arm / With her eyes as she stares at me / ‘I should have listened to my mom,’” and a chorus that turns accusatory: “Your hair smells like the ocean, baby / Where did you go yesterday?”

“The Black Hand” is presented as a “hard rocking communist house-party anthem,” and Rubinstien explains the posture behind it: “I’m not a card carrying Satanist, but this song is the closest thing we have to a ‘70s homage to things like how AC/DC mocked the Satanic Panic with ‘Highway to Hell.’ But, we’re working out real grievances through that lens. The big finish should’ve been ‘where all the drinks are free,’” he laughs.

“Keystone State” turns into a different kind of dread—what if the dream was the trap—with lyrics like “Could’ve had a couple kids / Could’ve fell in love again / Been a big fish in a little lake.”

View this post on Instagram

“666 Chicks” escalates into Russ Meyer-style horror imagery and political whiplash, including lines like “All the sick chicks in this sick chick city will die drowning / Will die in flames / Hail Satan / Will die assassinating men who try to keep them chained,” and “My grandmother Hannah used to throw Molotov cocktails at Nazis / and I’m paying ten bucks for coffee / and writing bad poetry / There’s no hope for me.”

Rubinstien’s related personal context is explicit, and he doesn’t soften the comparison: “My grandmother, Hannah, was in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in Poland and threw literal Molotov cocktails at literal Nazis,” he says. “And here I am, singing my little songs about wanting to be an impressive revolutionary or whatever, when she actually fucking did it. And her daughter, my mom, is like ‘maybe the Supreme Court will help. We gotta trust American institutions.’ And I’m like, ‘Your mom threw a fucking bomb at a Nazi.’ She’s like, ‘It’s not the same thing.’ And I’m like, ‘It kind of is!’ We’re getting there, and she’s starting to come around, which is how I know it’s getting bad.”

He also ties identity, politics, and danger together without euphemism: “Both of my parents are from Israel, and I have predictably consistent progressive, lefty politics. Jewish identity is super fraught in 2025 America. There’s huge teachings of social justice in Judaism, and yet Jews are being painted as the ones that are spearheading this American pro-Israeli genocide — on the supposition that it’s protecting people like me, when it’s actually making people like me far less safe. There are far fewer Jewish people in the United States than there are, say evangelical Christians, and the evangelical Christians are far more virulent in their support of Israel. They pay lip service to the idea that their support is to help Jewish people and fight anti-semitism, but of course the call is coming from inside the house. They clearly don’t care about the safety of Jewish people. And once this all goes pear-shaped, which it will, the Jews will be the easiest people to blame. The thing that makes me the craziest is that conservatives are doing all this to be like, ‘We’re protecting you.’ I’m like, ‘No, you’re fucking not! Fuck you!’”

View this post on Instagram

The “666 Chicks” video is described as directed by Rubinstien, framed as a cannibalistic horror film where young women overtake and replace the band members, starring Susi Matza, Emily Joy Lemus, Maddie Bernstein, and Jensen Wysocki (drummer of the all-female alt-rock band The Maraschinos). Rubinstien’s line on that is blunt: “The best punk is done by women right now.”

“This Place Sucks Ass” begins with Chapman’s six-year-old son Nolan screaming the title line. It’s described as a co-write between Rubinstien and Fleury, with Desrosiers’ teenage cousin Vivi Decareau on the chorus, and ends with the chant: “I rage, you rage / Trans kids deserve to see old age.” Rubinstien explains the coping mechanism inside the shouting: “The real question of the song is about our future,” he says. “It’s always kind of been like this, and there’s no prescription for a solution. It’s not like all we have to do is hug and commiserate. There’s a line I stole from Florence and the Machine, ‘you can’t carry it with you if you want to survive.’ We have to learn how to put that down… how angry we are. I carry a lot of anger with me, all day, every day. This can’t be my entire existence or I’ll die. I won’t be able to function as a human if I’m this angry all the time. What I’m saying by the end of the song is that you can scream ‘This Place Sucks Ass’ and then move on for a while.”

“The River” is described as personifying anxiety as something living inside you, with Rubinstien repeating: “Come be the creature in me / Until I’m Hollow / Protracted / A cavern / An echo / A liar.”

“Clever Cleaver” is the track the band openly nerds out on rhythmically. Rubinstien asks it like he’s still checking his own hands: “Am I playing in 4:4?” Chapman answers: “I play in 5:4. And then I did a bongo track in 7:4.” Desrosiers adds: “And Josh and I are playing in 3:4.” Rubinstien connects the structural “mess” to the song’s psychology: “The interesting part about that is there’s a connection to the lyrical content of the song. It was also a cool ‘what if’ that we all said yes to. We kept adding elements until we had this thing that sounds kind of like a mess. But also kind of like it was always meant to be like that.”

“Totally Depressed” gets described as talky, manic, and chorus-heavy, with Rubinstien singing: “You need to be medicated / Forcibly / You need a lobotomy / 50,000 volts of electricity straight to your brain / Something to keep you straight. / Oh it’s fine. Don’t worry mom. I don’t really want to die. / Just maybe life’s not worth being alive so long.” He says the intent behind that lyric was weirdly practical: “I put that verse in there so my mom would know I’m actually okay,” says Rubinstien. “It didn’t work. She’s still worried.”

“Red Rain Boots” is described as being about the eventual death of Rubinstien’s husky-pitbull mix, Chubbs, and Rubinstien frames the writing prompt in a way that tells you exactly what kind of album this is: “This came from a songwriting challenge from a friend,” he says. “She gave me the word ‘rain boots’ and she thought I’d write something nice. Instead I wrote a song about how one day my dog will die, and when that day happens I’ll march into Heaven to kill God for what he’s done.” Chapman hears the song as film before anything else: “To me, this sounds like a rock and roll Ennio Morricone movie that’s directed by Nick Cave. It has that vibe.”

The closer “Closer” is described as an epic in three parts: I. “Ajj Goes Electric (Shout Anarchy!!!)” / II. “The Black Hand, pt. 2: Fuck the Black Hand” / III. “It’s Over.” Rubinstien explains why it had to loop back on itself: “The last song references a bunch of other songs on the record. We reference like five other of the songs on the record. We wanted to make it feel like this whole thing was one idea, one fever dream, one concept, one thing that belongs together in this order, as opposed to just a collection of singles.” Desrosiers adds the final pivot: “And the very ending, we’re just like, what if it just became a Sabbath song?”

Chapman points to a specific structural influence: “Josh and I kept going back to Weezer’s quite underrated album Everything Will Be Alright in the End, which ends with a trilogy of songs called The Futurescope Trilogy. The third part is just all guitar riffs. We’re like, okay, after the song ends, there should be no lyrics and we should just riff for two and a half minutes, and that’s how we’re going to close the album.” Fleury underlines how it landed in the studio: “And amazingly, all five and a half minutes of that was the song we did in one take in the studio.”

Rubinstien also unpacks “Closer” as self-critique—anger turning back on itself, then trying to turn outward again: “‘Ajj Goes Electric’ is an acknowledgement that we’re pulling a riff from them, which is funny, because I think that song is already electric. I also wanted to write a song called ‘The Black Hand, pt. 2: Fuck the Black Hand,’ because once again, I think it’s funny. Then I look back on the previous songs of anger, protest and revolution, and think that I didn’t know shit. I’m an idiot. I can be as angry as I want, but I’m still just singing in front of people. I’m not actually doing anything. We also steal from The Long Winters song ‘The Commander Thinks Aloud,’ which is about the space shuttle Columbia blowing up. That’s where the lyrics, ‘The crew compartment is breaking up,’ comes from. And then ‘part three’ is ‘It’s Over,’ because the record starts with, ‘At Least It’s Almost Over,’ and now we’re at the end. It’s over. Play this record from beginning to end and the world will end. It’s like typing Google into Google and the internet breaks,” Rubinstien laughs.

And he closes the political logic of the record in terms of privilege and risk—who gets targeted first, and what they think music can still do: “Even if this country falls apart, we won’t be the first on the list to go to Gitmo. We’re white, we’re men and we’re all American born. That comes with a certain degree of privilege, and we want to use that privilege to spit in the face of the people who are doing really, really evil things to our trans homies, to our people-of-color homies, LGBTQ homies, and everyone else.

There could come a time when an album like this becomes illegal, that music like this will be considered terroristic speech and no longer protected by the Constitution. I hope that people remember that there’s more of us than there are of them, that the day this type of music becomes illegal is the day that a million teenagers buy guitars from pawn shops and start writing their own ‘Bad New Religion’ and ‘666 Chicks.’ Maybe there’ll be some anthem, right? Maybe some song or slogan will break through and be the rallying cry of the revolution. I don’t think it’s going to be our music. It would be awesome if it is. I want someone, somewhere, to write the song of the revolution and that to be of the rallying cry for people to stop all this fucking nonsense. We have to take the cartridge out, blow in it, and plug it back in if we’re going to survive this. Redo the government. Rebuild everything from scratch.”

View this post on Instagram

How they got here

Rubinstien grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, just outside Philadelphia, started guitar at 14, and formed his first band at 17. He describes Philadelphia with the kind of affection that only works if you’re half insulting it: “Philadelphia is a town full of scumbags,” says Rubinstien lovingly. “Everyone’s sort of a piece of shit in Philly. David Lynch called it a forgotten city. It’s a city full of great art, and the rent was cheap so people could survive as artists. I was always really inspired by Philly bands like The Dead Milkmen and The Teeth. It’s all part of the DNA of my songwriting. I wanted to be in those bands, or like those bands. I feel like I have an East Coast, unfriendly demeanor, a bit of a chip on my shoulder, especially on stage. Singing songs in front of people is basically like reading your diary. So my Philly defense mechanism is to start with a fuck-you-attitude as soon as I step on stage.”

View this post on Instagram

He moved to Boston for college, started Pray for Polanski, met drummer Dan Ramspacher, then moved to Los Angeles. “I was scared to move to LA,” he says. “It was a put up or shut up moment if I wanted to be a filmmaker. I spent five weeks touring with my friends and made a movie out of it.”

Rubinstien wrote, directed and starred in The Anchorite (2016) alongside Ramspacher, later directing shorts, music videos, and the feature film Lizzie Lazarus (2024). He arrived in LA “with lots of songs and no band,” and the band’s origin story is half coincidence, half Los Angeles logistics. “I found Rick on Facebook,” says Rubinstien, “but it turns out his brother was best friends with the brother of the bassist from b&d Confusion, and our high school bands had played shows together. When we started jamming in LA, he knew some of my old songs. We just clicked, and we’ve been playing music together ever since.”

They went through The Anchorite as a solo name, Chapman joining live, a band called Evil Exes, then regrouped with Desrosiers and Fleury as Jacob the Horse in 2016. Rubinstien explains how the lineup locked: “Mark was friends with my wife, and I knew him from his Boston band This Blue Heaven. He’d just moved from San Francisco to LA.” And Fleury’s origin story is basically “wrong instrument, right person”: “Josh auditioned for bass, but he was a guitarist first, and a riff machine. I wanted a second guitarist to play lead, and he was perfect. They both fit right in, and we started writing together.”

The band name comes from Rubinstien’s father Jacob and the nickname “Jacob the Horse,” which he learned about later from a family friend.

They recorded their self-titled album (2017) with Grammy-winning engineer Mark Rains, then tracked singles “Deaf by 33” and “Dead by 45” with Rains again. Rubinstien looks back at those political instincts as early steps that now read like a different country: “I thought 33 was so old when I wrote that song,” he says. “When Trump got elected the first time, we still had hope in us. I wanted to get away from songs about love and heartbreak. I hated assuming that people cared about my relationships. Now ‘Deaf by 33’ and ‘Dead by 45’ feel a bit naive and quaint.”

College Party Mixtape, Vol 1 (2021) is described as reflective—Rubinstien talking to his past self and a party-house memory loop. “If ‘Bohemian Rapsody’ came on, we knew the cops were coming and it was time to take off,” he says. “They’d always listen to the same mixtape over and over, and this is where I first heard Bomb the Music Industry, Jeff Rosenstock and Third Eye Blind. The album art is a homage to all the people we’d party with there, our wives, and our previous bands. This album has all these characters that are just frozen in time from different parts of our lives.”

During that era, Rubinstien left the country to teach filmmaking and worked on a project he describes like a cautionary tale, ending in the line that became the new album’s title: “This movie took three months to get started,” he says. “I almost got deported. The executive producer almost got his foot cut off. There were bribes. It was the craziest time of my life. It was this huge opportunity that was supposed to change my life. On the last day of shooting, it was taking forever to get this effects shot done. I was frustrated and went to the craft service table. A producer on the film, Harris, was there. I don’t think he cared about the movie at all. I sat there for a second and was like, ‘Harris, I worry that we’re making a bad movie.’ He just puts his hand on the table, looks at me, and says, ‘At least it’s almost over.’ That’s not what I wanted to hear, right? Not helpful at all, but I’ve taken that as a motto, or mantra, or whatever. It refers to our lives, like America is almost over, like the only peace that we’ll find is in death. And that’s how the album got its title.”

They connected with Jack Shirley while finishing that album—“Jack made every recording session feel like a special event,” Rubinstien says—and ended up recording At Least It’s Almost Over at Shirley’s Oakland studio.

If you made it this far, you already know what “Bad New Religion” is doing — now it’s just a matter of letting that single sit with you until “At Least It’s Almost Over” lands on March 20 and shows how far Jacob the Horse are willing to push the same panic, the same jokes-as-armor, and the same refusal to pretend any of this is getting better.