“Iarmhaireacht”, the new EP from Dublin’s Nerves, arrives August 15, steeped in layered grief, archival unease, and the sense that Ireland’s past is whispering directly into 2025. The title, Gaelic for “that uncanny loneliness you feel at first light,” captures the blurred line the band walks between the personal and the political, the literary and the sonic. With five new tracks and a denser use of sampling than before, this is the group’s first outing as a four-piece — and their most compositionally confident.

Having started in rural County Mayo, Nerves have grown into one of Ireland’s more unflinching live acts, sharing stages with The Jesus Lizard, Maruja, and HMLTD, and drawing early praise from outlets like Kerrang! and The Line of Best Fit. “Iarmhaireacht” builds on their 2024 EP “Glórach” with more abrasive production, further immersion into sample-driven storytelling, and lyrics that lean into emotional exposure without hedging.

As vocalist Kyle Thornton puts it, “If it feels like you’re exposing yourself in a very vulnerable way, that’s probably a good thing… that fear that you might feel is a good way of knowing you’re on the right track.”

“Takes A Second”, the EP’s most recent single, opens with looped static and slowly bends into a guttural collapse. The song sketches the final moments of a relationship strained by mental erosion, with production by Daniel Fox (Gilla Band) that carefully balances tension with minimalism. The band focused on creating “as much movement with as few notes as possible,” bending notes out of tune until they “create this sickening, super tense feeling.” It’s a calculated form of decay, and one that sets the tone for the rest of the release.

What distinguishes Nerves from others working in Ireland’s growing noise-punk underground is their deliberate use of archival sound. Throughout “Iarmhaireacht,” samples drawn from RTÉ news reels, folklore tapes, and podcasts act as secondary narrators — not decorative, but contextual. “The aim is to give more depth to the record,” says Thornton, “by either expanding on something I might only be hinting at in the lyrics or giving the cultural context to a personal problem.” These fragments tether contemporary mental anguish to mid-century rural despair, emphasizing continuity rather than contrast. “A recording from 1951 talking about how lack of jobs and emigration have left working class rural people feeling forgotten and abandoned has as much relevance in 2025 as it did then.”

This looping of past and present is particularly striking in the track “Neifinn”, which features a sample about a town near Thornton’s own home in Mayo. “It talks about the difficulties facing rural communities there in the 1950s, but they were exactly the same as everything I grew up hearing about our area in the 2010s and still now.” The slow economic collapse of Mayo — its post-2008 bleed-out — isn’t just backstory here, it’s formational. “It’s no place for young people anymore.”

Tracks like “Act of Contrition” and “Through My Chest” sit at the EP’s cinematic core, leaning on Nerves’ ability to control tension and atmosphere. Final track “Don’t Let Go” starts in ambient techno territory and ends in post-rock catharsis. Initially written with a heavier industrial feel, it evolved during live sets into something more exposed. “Now the outro is pure catharsis,” says Thornton. “It’s very satisfying live… it does feel like I’m exorcising something.”

Lyrically, Thornton draws more from novels than traditional lyric writing, inspired by Camus, Beckett, Flann O’Brien, and John Williams. Many tracks begin mid-thought, slowly revealing context like a diary that was never meant to be shared. Spoken word elements remain part of the toolkit, especially in places where the density of the language needs room to stretch. “I always tend to write more when I’m reading a lot,” Thornton says. “Sometimes I’ll look back through these pieces and repurpose lines to put into our songs.”

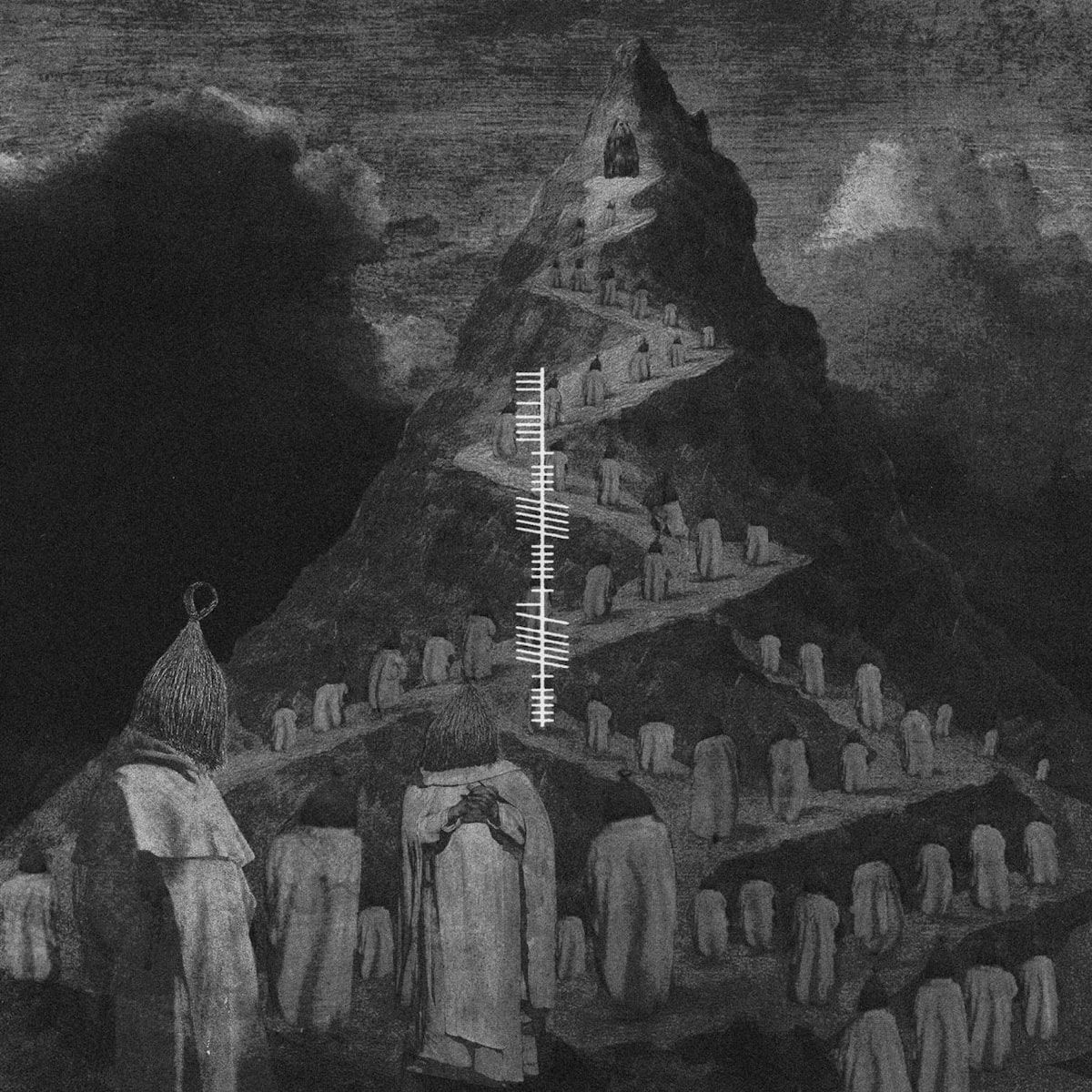

Culturally, Nerves reclaim Irish identity with a left-leaning slant: not as nostalgia, but as resistance. From Ogham-script artwork to wren-boy imagery and Irish-titled interludes, the EP gestures toward a shared cultural memory that was systematically suppressed under colonial rule. “Our pride in our country is never an endorsement of our government or of nationalism in general,” says Thornton. “It lives more in spite of that than anything else.” In a time when folk aesthetics are often co-opted by right-wing politics, Nerves flip the narrative — using language and symbolism not to retreat into the past, but to make it speak.

Daniel Fox’s production doesn’t redirect the band but strengthens what’s already there. “We usually come into the studio with a really solid idea of what the song is,” Thornton says. “It’s always nice to see Dan excited by something we are doing.” The process is collaborative but controlled, shaped by instinct, not improvisation.

As for what’s next, the band is already writing with an album in mind, doubling down on ideas introduced here but aiming for a broader palette. “We are trying to write a more varied array of song types while making our sound itself more focused.”

Below, Nerves talk in detail about using samples as cultural commentary, the erasure of rural Ireland, the use of Irish symbolism through a post-colonial lens, and the ways personal grief often doubles as political critique. Read on for the full interview.

You’ve said that “Iarmhaireacht” means that uncanny loneliness you feel at first light. Not to get too philosophical straight off the bat, but when did you first feel that specific kind of loneliness yourselves, and was it something that haunted or comforted you?

I’m sure I’ve felt this feeling many, many times, so to pinpoint the first time I felt it is probably impossible. However, I think the earliest one I can reliably remember is probably when I was a teenager, like 15 or 16 or something, going camping at a local lake with a load of our friends. One of those nights where there’s a lot of teenage drama going on. Added to that, it was probably one of my first times drinking, and the session went on until late in the night. I remember for some reason I never went to bed even though everyone else had, and I just wandered around the beach at dawn feeling this profound sense of sadness that I couldn’t really explain. It was beautiful in a way, watching the sun peeking up past the mountains, sitting on this beach in North Mayo feeling the weight of how my life was changing from a much more innocent time to something more mature but chaotic. I don’t know if it was haunting or comforting, it felt somewhere in between at the time, and I’m quite happy remembering it that way.

The samples you used, the archive tapes, RTÉ news fragments, pub-room mutterings, they’re more than texture, they’re almost like secondary narrators in the songs. How do you know when you’ve found the one, that perfect bit of old Ireland that resonates with what you’re writing in the present?

The way you’ve described them as secondary narrators is perfect, because that’s kind of how we aim to use them. Obviously the way they sound and what’s going on in each of them factors in a lot, but the aim is to use them to give more depth to the record, by either expanding on something I might only be hinting at in the lyrics or giving the cultural context to a personal problem that might be the theme of the record. That, and also to show our fascination with folklore and memory.

It’s hard to say how it clicks when we’ve found the one, because we go through so much material to find what we eventually use, and the reasons why they are being used might vary from sample to sample. Say with the intros to the two EPs, on Glórach we found this sample that talked about mental health in the west of Ireland, and we immediately felt like the message it conveyed was as relevant now as it was then. But also, whoever soundtracked the show it featured on used some very creepy synth music on top of it that sounded so otherworldly and strange. When we heard that being introduced, we couldn’t believe our luck to have stumbled across something with two incredibly interesting elements. That sample was so old that the soundtrack was surely one of the earliest uses of synth in soundtracking.

The intro to Iarmhaireacht, by comparison, was taken from a podcast I was listening to from the National Folklore Archive, where a collector is telling someone of a conversation he had with a man who claimed to have met with the fae. His rendition of what the man said felt so haunting that I knew it deserved a place on the EP in some capacity.

There’s this eerie sense in the EP that the past isn’t even past, that these voices from 1951 are talking straight into 2025. Was there a moment, during writing or research, where that overlap really hit you hard?

Yeah, with the samples we choose in particular, we try and draw a parallel between the issues that faced Ireland in the past and what we’re experiencing as a country now. When I found the Neifinn sample originally, that sense of being trapped in this sort of time loop hit me hard, because the sample is specifically about a part of Mayo very close to where I’m from. It talks about the difficulties facing rural communities there in the 1950s, but they were exactly the same as everything I grew up hearing about our area in the 2010s and still now.

Do you feel like growing up in rural County Mayo gave you a sharper lens on these cycles of erasure and economic exile, like you could see the hollowing-out happening in real time?

Yeah, I suppose. Not necessarily a sharper lens on it, because I don’t feel like I’m in any position to propose any solutions. But yeah, I’ve spent my life watching my hometown and the surrounding towns slowly degrading, especially since 2008. It’s no place for young people anymore. Every time I go back home, I hear of five more people I knew from school emigrating to Australia or somewhere like that. It’s very frustrating to watch a place you love get hollowed out over time, and then listen to politicians pontificating on how much better we are doing as a country now.

There’s such a disconnect between the people in charge and the people who live in these areas, and it kind of leads you into this depressing mindset where it’s hard to see how things could start to get better for rural Ireland when the government can only think as far as the M50 motorway.

The record seems to drift between something deeply personal and something clearly political, but not in an obvious protest-song way. When you write, do you draw a line between personal pain and public rot, or do you find they always bleed into each other?

All my songs come from a very personal place, and I very rarely plan any sort of larger political context when I’m in the middle of writing them. I tend to draw these connections after the fact. I’ll realise that the personal problem I’m addressing in a certain song is a symptom of this wider societal problem, and then we might use the samples to draw attention to these connections.

I’d be of the opinion that all music is inherently political anyway, and my way of writing politically has to come from a very personal place. I respect people that can write more straightforward protest songs, but it’s just never been the way I go about things.

There’s this Beckett-esque quality to your lyricism, that mix of the absurd, the bleak, and the oddly tender. Do you feel more at home in literature than music when it comes to shaping your lyrical voice?

Yeah actually, to a certain extent I feel like I do. I always tend to write more when I’m reading a lot, and I tend to write a lot of lyrics for songs and think about how I’m going to make them all fit a little bit later. I suppose that’s why I started doing more spoken word–styled vocals initially, because that way I was able to fit more lyrics into a shorter space.

I do write outside of lyrics, but nothing very structured, pieces that are somewhere between poetry and prose. Then sometimes I’ll look back through these pieces and repurpose lines to put into our songs. I’m also a serial quoter. I have so, so many quotes that I’ve jotted down from books I’m reading, and they will often end up in our songs. Yeah, I suppose in a lot of ways I’m way more influenced by literature than lyrics when I’m writing.

Were there any novels, old dog-eared books, or stories passed down in the family that unexpectedly shaped how you write lyrics now?

I actually don’t think so, not through the family, anyway. My parents are both big readers, but I would say our tastes in books are fairly different for the most part. I don’t tend to read many lighthearted books.

Some parts of “Iarmhaireacht” feel like they’re trying to exorcise something, others feel like they’re surrendering to it. Do you ever argue as a band about how far to go emotionally in a track? Like, when is too much actually too much?

We very rarely argue about that because I feel like we are all on the same page in terms of letting that stuff out. I think we all have a sense that if it feels like you’re exposing yourself in a very vulnerable way, that’s probably a good thing. That fear that you might feel is a good way of knowing you’re on the right track. If there’s a “too far” for us, I don’t think we’ve found it yet. I think we are all in this to let a couple of demons out.

In “Takes A Second,” there’s this slow emotional collapse mirrored in the sonics. How much of that tension-and-release structure comes from deliberate production choices versus you all following a shared emotional instinct?

With that bridge section of Takes, I think the tension-building and releasing aspect was actually pretty intentional. Around the time of writing that, we were trying to create as much movement with as few notes as possible, so there are parts where we’ll just hit one note and bend it almost entirely out of tune, so that the two guitars are almost playing the same note but not quite, and it creates this sickening, super tense feeling. Most of our playing is very instinctual, but we will come in with certain ideas like that, a vague concept of what it is that we want to achieve, and then we just let instinct take over.

That final track, “Don’t Let Go,” hits like a last dance in a crumbling room. Ambient techno, post-rock, something almost elegiac. How did that track come together, was it born in jam sessions or pieced together like a sound collage?

It definitely came together in sections. Originally, ambient techno was absolutely the main influence, trying to replicate the feeling and sonics of those tracks with guitars, drums, and bass. The first half of the song has been set in stone for a very long time, but the second half used to have a very different feel to it. I suppose it went into something more like a heavy industrial part, still super dancey but very riff-oriented.

After playing it like that live for a long while, we noticed that due to the lyrics, the samples, and the general feeling of the first half of the song, the whole thing felt a lot more emotional and vulnerable than we had expected it to. So we decided that the second half needed to match that emotional intensity that we had built up over the first half. Now the outro is pure catharsis. It’s very satisfying live, that point in the set in particular does feel like I’m exorcising something.

What was Daniel Fox’s role in shaping the architecture of this record? Did he challenge you on anything that you initially resisted?

Not really. Us and Dan have been working together for a couple of years now, so we are all very familiar with each other. We understand his work process, and he gets our sound and therefore knows what to do very quickly. So usually the whole process is super smooth. We also usually come into the studio with a really solid idea of what the song is, so there’s not tonnes of room for last-minute arrangement changes or anything. Still though, it’s always nice to see Dan excited by something we are doing in the studio.

You lean into Irish culture, language, and symbolism hard, Ogham script, Wren-boy costumes, Irish-titled interludes, but with a clearly inclusive, left-wing lens. In a time when national identity gets hijacked by reactionary forces, how do you navigate that tightrope between pride and politic?

I think for us we try and come to it through a post-colonial sort of viewpoint. For centuries our culture and traditions were torn apart by the British, and even though we have been mostly independent for the last hundred years, the work of bringing this culture back is still very much ongoing. We are interested in these things as a way to find out what it means to be Irish, and we present it in a way that I hope says, “Hey, this is us, you’re welcome to share in it.”

Seeing the right-wing adoption of folk culture across other countries is frustrating, but I also don’t fully believe it in Ireland, because any right-wing “Ireland for the Irish” folk you meet generally have no interest in folk culture and can’t speak a lick of Irish. It’s all posturing. Any people that I meet that are genuinely interested in learning more about our traditions and culture are usually massively left-wing. Our pride in our country is never an endorsement of our government or of nationalism in general. It lives more in spite of that than anything else.

How do you feel about the current wave of Irish artists reclaiming Gaelic and older traditions not as nostalgia, but as tools for now, for resistance, community, and storytelling?

It’s amazing to see, and it’s the right direction to take it in. If you treat these things as nostalgia, you relegate them to a bygone time. Whereas when you use the language and the symbolism in a straight-up sincere way, then it becomes a living, breathing part of the culture again. That’s the only way these things will really survive, and I think our traditions lend themselves to being tools for resistance and storytelling, because these are things that are baked into the fabric of Irishness, in my opinion.

Is there any part of Irish culture, visual, oral, literary, or even culinary, that you feel hasn’t been mined enough by underground bands yet?

Some more songs about the GAA would be good.

Dublin’s underground is shifting fast, more abrasive, more interdisciplinary, more politically sharp. Who’s around you right now that’s pushing things forward, and who surprised you in 2024 or 2025?

Bands like our friends Gurriers, sonically and politically, are pushing things in the right direction at the moment. For Those I Love as well is making beautifully moving music. For surprises, The Null Club is sonically one of the best acts I’ve seen in a long, long time. I was absolutely blown away at the headliner in Workman’s a few months back.

Beyond Dublin, any off-radar acts from rural Ireland or elsewhere that deserve way more noise than they’re getting?

Pixie Cut Rhythm Orchestra is one of my favourite bands and also from Mayo! Pebbledash from Cork are incredible! Casavettes from Limerick too!

What’s your favourite show you’ve played where you felt the audience got what you were doing, not just the sound, but the entire haunted emotional architecture of it?

I feel like they really understood us at our last Paris show during Supersonic Block Party. There was just a wild energy in the room, and even though it was a sweaty basement venue and everyone was in festival mode, when we went super quiet in songs like Act of Contrition or Don’t Let Go, everyone just paid full attention. They weren’t just there to push each other around to heavy noise rock, they really got us.

When you’ve shared stages with bands like MARUJA or THE JESUS LIZARD, did you notice any shared DNA between you, or are you all coming from totally different psychic landscapes?

I feel like us and The Jesus Lizard share some DNA for sure, but we are doing very different things musically and tonally. Whereas with Maruja I do really feel like we have a large connection in terms of where we are pulling from and how we want to convey our ideas.

Do you ever imagine what kind of band you’d be if you hadn’t left Mayo, if the whole thing stayed in a shed behind a petrol station somewhere?

We’d be a pretty decent punk band maybe, but I don’t think we would have gotten nearly as loud as we are now. I also probably wouldn’t have used a bow on my guitar at any stage.

Are you writing with any future themes in mind already, or is Iarmhaireacht the kind of thing that needs to echo out and settle before you know where to go next?

No, we are definitely writing at the minute. I suppose we are writing with an album in mind at the moment and doubling down on a lot of ideas that Iarmhaireacht displayed. We are trying to write a more varied array of song types while making our sound itself more focused.

And last one — if a stranger walks up to you after a show and says “that made me feel weird, but I don’t know why,” would you consider that a success? Or do you still hope to be understood?

I have had this exact thing happen to me and I think it’s class, honestly.