When Joey, once the guitarist for the Canadian screamo band Todos Caerán, quietly uploaded a new self-titled album under the name “Distant Mirror,” it marked the end of a long, private decade. “The goal for this project was to try and do as much as possible by myself,” he said. “I learned how to play drums, learned how to do vocals without destroying my throat, learned how to record, mix, master, built most of the gear I used.”

He calls the sound “emo riffs over blast beats,” a screamo–black metal–post-metal–shoegaze mashup. But for Joey, the album is less about genre and more about survival. “It took a couple years but it’s done and I’d like to share after all of that effort. I was initially worried that, because I basically put this together in private, there was the distinct possibility it would turn out to be complete dogshit. I don’t think that’s the case though.”

The Todos Caerán days

Joey had been writing music since he was a teenager. “Through my late teens and into my mid-20s I played in a number of bands, the most well known, at least by the standards of the punk/hardcore/screamo music scene, was Todos Caerán. We wrote a bunch of records, toured a bunch of countries, and played hundreds of shows (sometimes to dozens of people).”

By the end of Todos Caerán, he was juggling grad school, work, and worsening anxiety. “I was pretty unhealthy for most of the years Todos was active. Thirty seconds of running or a few sets of stairs would leave me winded.” In 2012, he bought a mountain bike to fix his cardio and started climbing soon after. “When Todos finally broke up I was actually pretty relieved. Practicing, performing, and recording had started to feel like a chore and riding a bike in the woods felt liberating.”

He stopped going to shows and barely touched his guitar. Years later, he would look back on that time as a necessary distance. “Now, almost a decade-and-a-half later, I understand how important exercise is for emotional regulation. I’ve got ADHD, replete with all the strange accompanying symptoms like aversion to certain textures and sounds. Exercise brought most of the symptoms under control so I was experiencing unimpaired mental capacity for the first time in years.”

Flight west

In 2017, Joey moved to British Columbia for a job as a digital literacy and makerspace librarian. “It was cool having a job that, ethically, felt concordant with the values you develop as a punk,” he said. “I got to play D&D with teens, buy books, taught seniors to use computers, helped people struggling with addiction and homelessness — all for free.”

Still, he clashed with the system. “Public libraries, at least in North America, operate with organizational methods borrowed from the business world. Top-down management; no agency for employees.” His free time became recovery. “I was spending all of my free time outside in the woods or at the climbing gym decompressing. I’d go months without even thinking about playing my guitar.”

When the pandemic hit, he was home again, guitar hanging beside his desk. “I decided to pick it back up and, rather than noodle, I started practicing scales.” By fall 2020, his first child was born. “I bought an HX Stomp so I could practice while he was asleep.”

Living in the end times

He began writing again, slowly. Then came 2021. “Fuck 2021,” he said flatly. “As I was trying to adapt to being a dad and struggling in my job after a forced return-to-office mandate, the interior of BC dried out.”

The description that follows reads like a scorched diary entry. “There had been some apocalyptic fire seasons here in 2017 and 2018 where we went weeks without seeing the sun. At its worst I couldn’t see across the street. The destruction of wilderness from those fires is difficult to comprehend. 1.2 million hectares of land burned in 2017. 1.35 million in 2018.”

In 2021, things worsened. “Lytton, a cute village that sat on a bench above the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers, where I used to teach technology classes, set a record of 49.6C. The town was completely levelled by fire the next day.”

He recalls driving through Monte Lake after it burned: “It was a patchwork of smoldering ruins in an alien landscape. The burned trees looked like stubble on the hillsides.” Floods followed. “Without the trees to stop erosion, the extreme rainfall brought entire hillsides down.”

These events dug deep into him. “If there’s any throughline in my music it’s from the desperation inspired by watching beautiful places I love burn down. It’s from getting hopes dashed as I tried to establish myself in a career that wanted to exploit my labour. It’s from getting increasingly radicalized by corporations that are trying to transform our society into a laissez-faire hellscape.”

Distant Mirror

In November 2021, he started a new job as a collections librarian at a university. “I negotiate access to resources for students and staff with multi-billion dollar publishers. Publishing corporations are amoral and extractive but I have a ton of freedom in how I do my work. I’m an activist librarian — I speak to other librarians and academics about corporate encroachment and monopolism. I’m mad all of the time and excited about it — it’s interesting and strangely motivating.”

He and his partner were expecting another child, so he tried to finish a few personal projects. “I finished wiring up an amplifier I started building in 2013, which inspired me to start building guitar pedals again. I wrote a bunch of songs, built myself a baritone guitar.”

He realized a full album might be possible. “I started relearning how to play drums after more than a decade because programming them seemed like a good way to get carpal tunnel.” Those songs became “Distant Mirror.”

The name comes from Barbara Tuchman’s 1978 book A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. “Fourteenth century Europe was contending with disease and climate disaster,” Joey said. “I saw social and environmental parallels. Then, like now, the wealthy were completely insulated from hardship as society broke down around them.”

He built most of his recording gear himself. “Through winter and spring that’s what I did. I’ve always played with a large pedalboard for maximum tonal flexibility and this new setup ended up working really well. I ran everything directly into a recording interface. I still prefer a tube amplifier — you can’t really beat the sonic punch that comes from moving air — but recording directly into an interface is easy and I didn’t have to buy or build microphones.”

Then came the crash. “I was riding my bike on a trail I’d done hundreds of times. A rock dislodged under my front wheel… My front wheel exploded and I was flung over my handlebars.” He broke toes, slashed his arm open, and ended the day in the hospital. “I wasn’t able to play drums for a month or so as I healed.”

By fall, he was recording drums and teaching himself to mix. “I went through dozens of mixes tweaking everything. It took me almost a year to get to a place where I felt like mixing made sense. I intentionally left some of the rougher parts. There are spots where you can hear the tempo waver, some choked notes, string noise. I like artefacts in a recording that demonstrate a human was playing the instruments.”

Lyrics came from his friend Amy.

“She’s better at conveying abstractions through language than I am,” he said. His partner contributed vocals on “sometimes come the mother, sometime the wolf” and “she who sends up gifts.” When illness made it hard to record, Joey decided to take on the rest. “I tried recording vocals for one song in May and immediately annihilated my throat… I spent a few weeks reading about vocal technique and warmup and got to a place where I could perform comfortably.”

Then he got hurt again. Another bike accident. “I ended up taking the impact on my ribs and something broke. For all of June I had a strange gargle in my lungs… I couldn’t take deep breaths for about a month or two.”

By August, he was healed. “Final mixing and mastering went smoothly. No injuries. No illness.”

can be fatal. Not pictured: the unreasonable amount of blood that came out of my body.

The life of an internet musician

Releasing an album now felt like a new world. “Even though it hasn’t been that long, the landscape has changed dramatically since 2010–2014. There are fewer platforms that host music or connect musicians with fans. The platforms that do exist want to squeeze musicians for a cut of their profits.”

He reflects on how music discovery shifted. “My go-to promotion strategy used to be submitting music to blogs. Now it seems like blogs are so inundated with requests that getting a spot as a new artist is a challenge.”

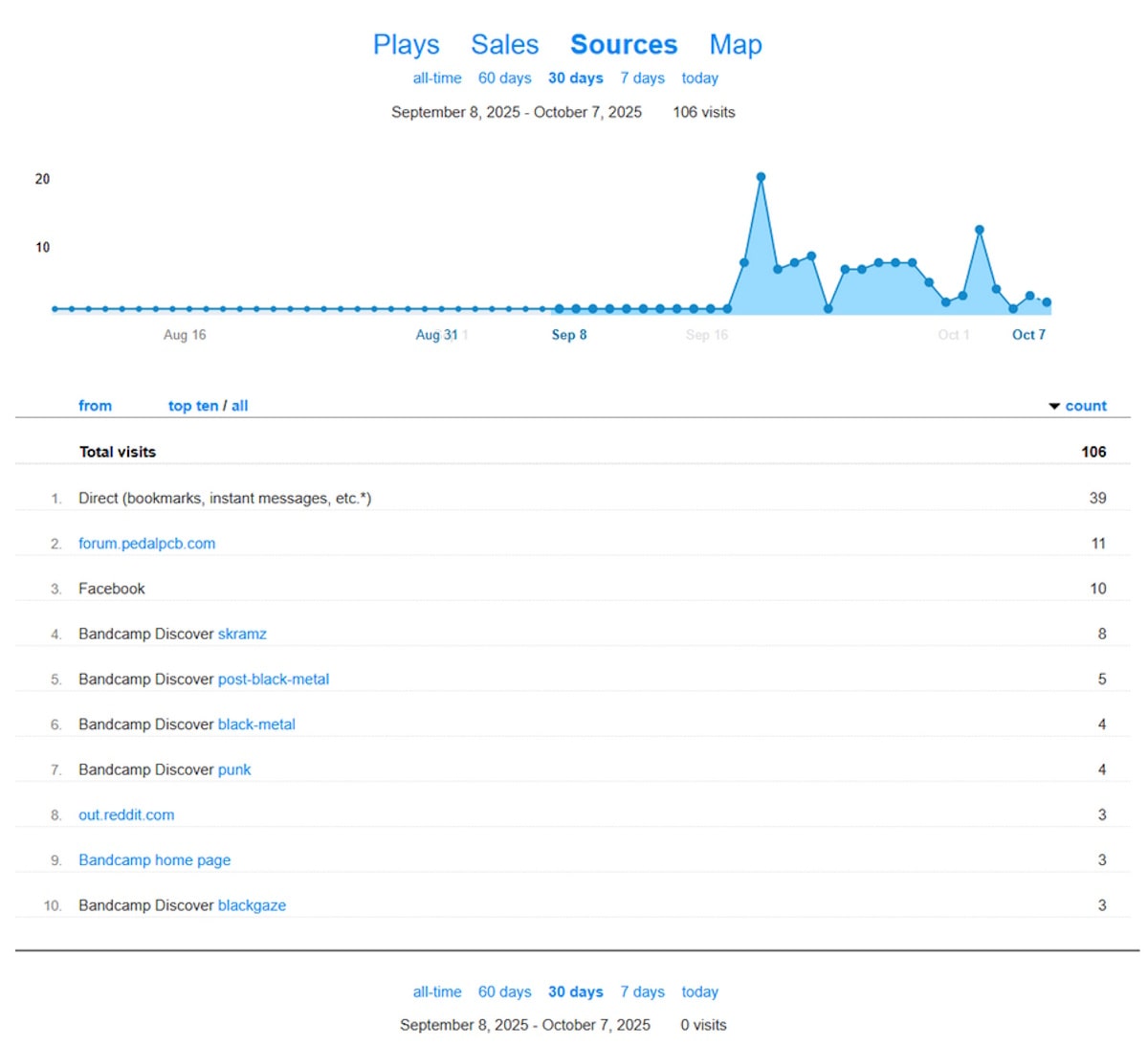

Still, he’s experimenting. “I’ve been hosting my music on Bandcamp, which provides some data on incoming web traffic.” The numbers, he said, were “roughly equivalent to what my first band would see a few weeks after uploading songs to MySpace in 2007. Back before we knew how to write music.”

He’s skeptical of social media reach. “Because of the way Facebook throttles views until you pay them, only 99 people ‘saw’ the post. Reddit was similarly bad.”

He laughs at his own aesthetic mismatch. “I let my son do the artwork. It’s personally meaningful but the design and colour-palette are somewhat off-brand for a metal (-adjacent) album. I think, if I want to fit in, I’m supposed to take a black-and-white picture of myself in makeup holding a sword?”

Joey hasn’t uploaded to Spotify or YouTube. “I don’t like how Google conducts business. I can’t help but feel like there’s some degree of SEO and ‘hustle’ required to do this as a single-person operation. I don’t remember having to overcome these systemic barriers companies have installed to essentially charge a toll on musicians.”

He’s philosophical about it. “The effort required is difficult to justify when I’m doing this out of interest, not to build a career. I’m going to keep making music, even if nobody listens to it. I’ve got another album in the works. For now I hope you’ll enjoy Distant Mirror’s s/t.”

Joey’s music doesn’t chase a scene so much as it documents a life — one that’s burned, scarred, rebuilt, and still quietly working through the noise. “Distant Mirror” feels like an unfiltered continuation of what Todos Caerán once hinted at — the same emotional gravity, but refracted through solitude, adulthood, and the slow processes of injury and repair. It’s handmade in every sense, from the circuitry on his pedals to the cracked edge of his voice.

There’s no campaign behind it — just a person rebuilding an identity through sound. The imperfections are the point. You can hear the room breathe, the timing shift, the hands at work. It’s music that exists because it had to, made by someone who has learned to find meaning in making things from scratch, even when no one’s watching.