Season to Risk spent the early 90s on the road (see their touring in van survival guide here), building a reputation as a young band thrown into heavy company — Killdozer, Unsane, Neurosis, Prong, Killing Joke. By the time Columbia Records signed them, they had one album behind them, radio play, MTV rotation, and the kind of upward draft that usually pushes a group toward the market’s center.

Instead, they took the budget, went to Brooklyn, and made “In A Perfect World” with Martin Bisi — a producer better known for sculpting noise than smoothing edges.

The album has been out of print for thirty-one years, and its return came as a remastered, limited edition reissue set for Record Store Day in November 2025.

The story behind the record still tracks with how the band describes it today — a document made by people who felt more interested in following a crooked instinct than fitting into a wave of radio rock. Singer Steve Tulipana puts it plainly: “The experience of living with Martin Bisi for an entire Summer while making this record was an opportunity of a lifetime.”

The sessions happened in Bisi’s cavernous, subterranean studio, once a Civil War–era munitions warehouse, where the acoustics leaned into the group’s heavier impulses. Guitarist Duane Trower still remembers how much the space shaped the sound: “Bisi’s studio… was a welcome cacophonic room that helped shaped the sound. As was the wool clad ghost that we saw, helping us put the finishing touches and mood of this record.”

The lineup at the time included the first appearance of the Paul Malinowski and Jason Gerken rhythm section, later known through their work in Shiner. The band lived in New York for the summer of 1994 to finish the album before Gerken left for commitments with Molly McGuire.

Once the recording wrapped, they brought in drummer David Silver and toured the material for the rest of the year. Silver still sees that era through the lens of constant movement: “We became a really tight unit, able to set up in five minutes and melt faces, and then get off stage even faster.”

Talking to the band now, three decades out, you hear the same mix of distance and clarity.

Tulipana sees the record as part of a longer personal arc: “Thirty years ago the music / art was vital and angry… you wanted to jump out of your skin and become something altogether not you, which is what you become thirty years on.” Silver frames it through the live grind; Trower sees the whirlwind of touring, the scramble to prep Gerken for the studio, and the uncertainty of what their label expected from them.

The larger question — whether they were trying to out-weird the scene or simply reacting to it — comes with equally direct answers. Tulipana says they pushed their own limits: “More intricate beats, layers and chaos… on ‘In A Perfect World’ it was brazen.” Silver connects those instincts to the members’ backgrounds in 80s hardcore and punk, and to the underground bands who shifted the vocabulary of heavy music: the Jesus Lizard, No Means No, Slint, Rodan, Don Caballero, Barkmarket. Trower just says he’s always been drawn to music where melody and chaos pull at each other.

Their summer with Bisi has taken on its own mythology, and each member’s memory of it lands differently. Tulipana talks about wandering New York alone, dropping into bars, meeting strangers, and realizing how much that period forced him to look at people more closely.

Silver remembers arriving in a broken van, living in a tent, and suddenly finding himself inside a studio where half of his record collection had been made. Trower remembers watching a car outside the studio get stripped piece by piece over the course of their stay, and catching Drive Like Jehu’s last CBGB shows on nights off.

The band is blunt about the label side as well. Tulipana says Columbia didn’t quite know what to do with them: “I think they wanted to try and figure it out but it was just too hard.” He recalls conversations that hinted at attempts to “form” the band into something more manageable, though nothing ever turned confrontational.

Silver remembers label reps warning them their album would land in the “Other” bin because they refused to call it punk or metal. Trower says they expected pressure to make a pop record, but Columbia mostly let them run, even if they couldn’t categorize it.

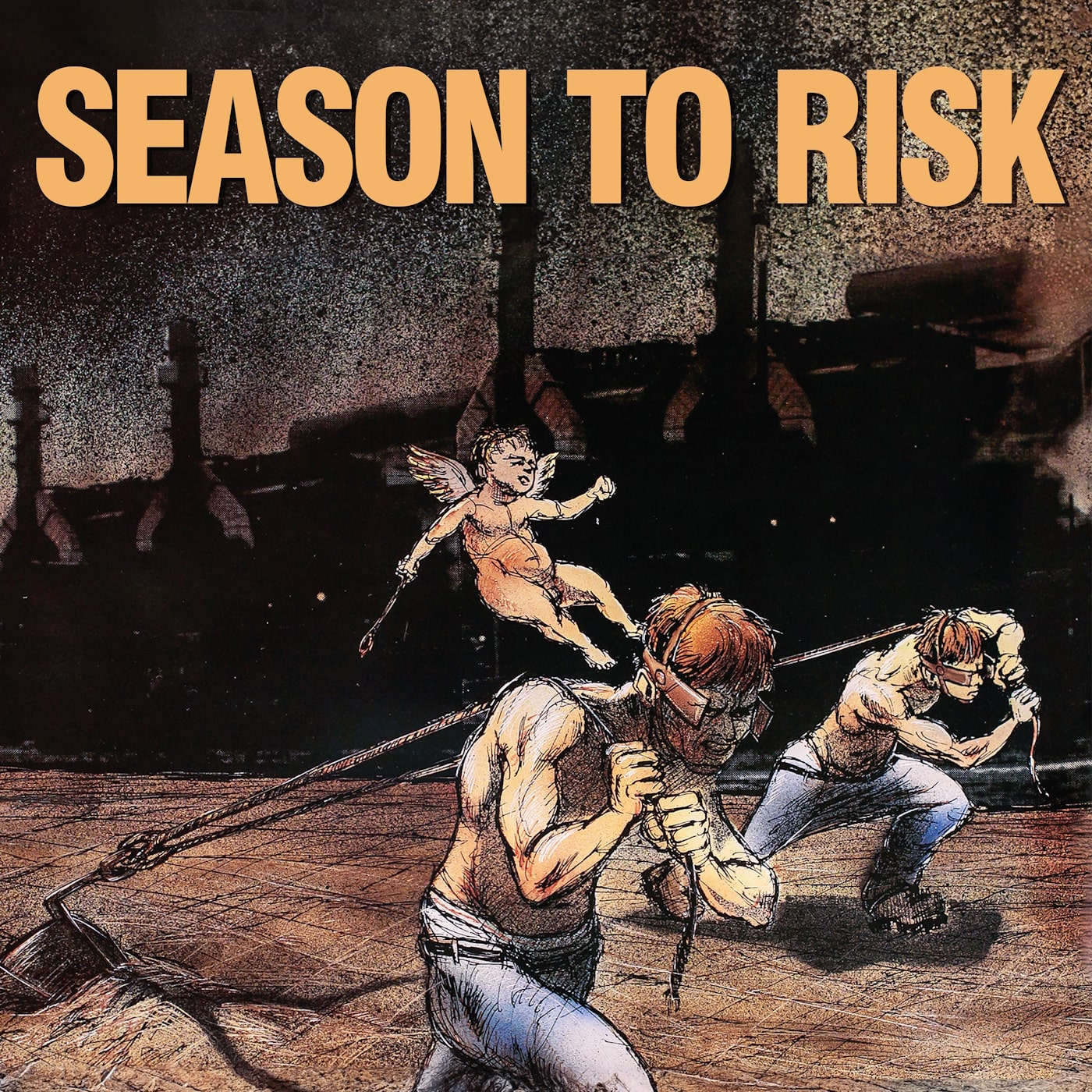

The artwork — Derek Hess’s stark, dystopian illustration — remains a defining piece of the album’s identity. Tulipana says they gave Hess the rough mixes and full freedom: “We always liked confusing the message. I feel it forces someone to make their own meaning.” Silver reads it now as a portrait of working-class collapse fused with apocalyptic fantasies. Trower ties it to industrial tension and the feeling of being trapped inside a mechanical cycle.

The 2025 reissue, remastered by Trower at Weights & Measures Soundlab, aims for clarity without sanding off the raw edges. It arrives as a limited edition of 1,500 copies with handwritten lyric inserts and new line art by Hess. It also lines up with a run of West Coast dates alongside Sisters this November and December.

Below, the full interview dives deeper — the making of “In A Perfect World,” the summer in Bisi’s studio, the label pressure, the artwork, and the memories that still hang in the room after thirty years.

When you look at In A Perfect World now — thirty years later — what do you feel first: pride, nostalgia, or something heavier that still sits with you?

Steve: Looking back thirty years cannot but bring up some nostalgia and pride but moreover it forces one to reflect on what has been the totality of your adult life. Thirty years ago the music / art was vital and angry, you wanted to jump out of your skin and become something altogether not you, which is what you become thirty years on – another person wholly. For me, maybe onto my third or fourth person! This record was personal but more so it was an art piece. That’s how I approach each record I’ve ever been involved with. There are characters that are informed by your personal experience and expressions that are of that character but outside of you.

David Silver (drummer): I’m proud of the live show we did touring for a couple years nonstop playing this record live. We became a really tight unit, able to set up in five minutes and melt faces, and then get off stage even faster. We got our act together and became lifelong friends in the process.

Duane Trower (guitar /synth):It definitely marked a point in time that was a whirlwind for us. We were so busy touring and getting ready to record this album. Then last-minute getting Jason Gerken primed for recording these songs, as well as getting settled into Martin Bisi’s studio and wondering what Columbia was expecting from us.

Back then, you were living inside that post-hardcore moment where everyone tried to.. let’s say out-weird each other. When you listen to those recordings now, do you hear a band chasing something new or one just reacting to the noise around it?

Steve: I think any good artist is always trying to out-weird themself! We were consciously trying to push the physical limits of what we could do when we were creating this album. More intricate beats, layers and chaos. I think we constantly try to chase something new. Sometimes it is more subtle but on In A Perfect World it was brazen. In my opinion.

David: All the band members came from actual hardcore and punk bands in the 80s. And it was time to move on from the typical riffs and beats and try to invent something new. Certain bands made waves through the underground and influenced songwriting for sure, some more obvious like The Jesus Lizard and No Means No, but also Slint, Rodan, Don Caballero and Barkmarket.

Duane: I have always liked music that was weird and still worked as a whole. Melody vs chaos and the balance of tension and release is huge also.

That summer with Martin Bisi in New York — it’s almost folklore now. What was the strangest or most human part of that time that didn’t make it into any interview or liner note?

Steve: I think each of us would have a different answer here. I was living my NYC fantasy and going out every night. Sleeping wherever I landed. I would go to bars all over the city by myself and end up in some interesting and odd places and spaces with unique people. I learned a lot about myself. Some things that weren’t too pretty upon reflection. Typical “rock” shit – sex, drugs and alcohol. But I also learned to see people. Really watch them and understand that there are so many different types. Helped me on my growing up part of my life. I guess. Late night conversations with Martin Bisi were amazing. He was so full of interesting stories and reflections. And questions. I learned to keep asking questions. Does that make sense? Now I’m def. feeling nostalgic! Ha!

David: My experience that Summer was poverty. I went to Bisi’s studio for my audition to join the band, in a van that broke down halfway to New York. I was living in a tent in the woods, running an illegal warehouse club that just got busted. The opportunity to suddenly be at Bisi’s, where most of my record collection was created, was a pivotal turning point for me.

Duane: Being in Brooklyn was a fun experience. Park Slope was a cool neighborhood, even though we saw a car get progressively dismantled down to only a frame on blocks while being parked out front of the studio! Seeing a handful of shows when we had downtime was fun also. If I remember correctly we saw Drive Like Jehu’s last few shows while they were at cbgbs.

You used major label money to make one of the most uncommercial records on that label. Did you ever get the sense that Columbia didn’t fully know what to do with you?

Steve: 100%. I think they wanted to try and figure it out but it was just too hard. There were conversations that were kind of sly, I think, looking back at it. They had me meet with the producer David Kahn one night when they’d flown me out to NY to do a bunch of press meetings at Sony HQ. He pulled up some tracks and we chatted about the songs, the meaning, my ethos etcetera. At that point I didn’t know my music history. I wasn’t aware of his story and I just felt like he was trying to see if they could “make” something out of me or the band. Form it more. I’m guessing he got the vibe that we weren’t tameable. It wasn’t too long after that that we were dropped now that I think about it. We’d already told Donny Ienner that we wouldn’t do a remake of Mine Eyes for the 2nd album and we just didn’t play the ball they wanted. Nothing was mean spirited or boldly defiant. No one tried to make us anything we weren’t. It was just at the edges. And in the end, they cut us loose. To be honest, I don’t blame them one bit. Ha!

David: I remember conversations from label guys about the record warning us the album will “have to go in the Other bin” in record stores, because we refused to let them call it punk or metal. There was no such thing as this music 30 years ago. Post-hardcore and math rock were happening, but they weren’t named yet. I heard a track recently from the Cyberpunk 2084 game soundtrack that sounds like it came off this album.

Duane: Yeah we fully expected Columbia to try to persuade us into making a pop record, but realistically they were letting us do our thing, even though they didn’t know exactly how to pigeon hole it.

The cover art still feels unsettling — half industrial nightmare, half biblical fever dream. What were those images supposed to represent to you at the time?

Steve: We gave the rough mixes to the artist Derek Hess, who had promoted shows of ours in Cleveland for years at this point. He was becoming quite lauded at this point. We gave him carte blanche. We always loved his artwork. The title was something our manager would always say and we thought the juxtaposition worked. We always liked confusing the message. I feel it forces someone to make their own meaning and add a personal layer to their experience with the music. Derek nailed it.

And when you see it now, do you read it differently?

Steve: I don’t. It still works. It’s of the time. Have you seen the video for Bloodugly that is basically a live action version of the artwork. It’s NOW!

David: To me, it’s a “perfect” working-class suffering image for the late-stage capitalist meltdown we all knew was coming, mixed with superstitious delusions hoping the apocalypse will cleanse the world, but save a chosen few. The boomers plundered the world, now they get to go to heaven.

Duane: We wanted the angst of an enslaved capitalistic world mixed with mechanical factory rhythms. Derek nailed the images.