In the early 1980s, if you wanted to be part of something, you had to leave the house. You wrote letters. You waited. You photocopied pages by hand, stapled them together, and sent them out with stamps and phone tokens. Paolo Palmacci remembers that world from the inside, not as an observer but as one of its many moving parts. Four decades later, he is methodically reconstructing it online—page by page, address by address—through Fanzinet, the 1980s Italian fanzine mapping project hosted on his blog Capit Mundi?.

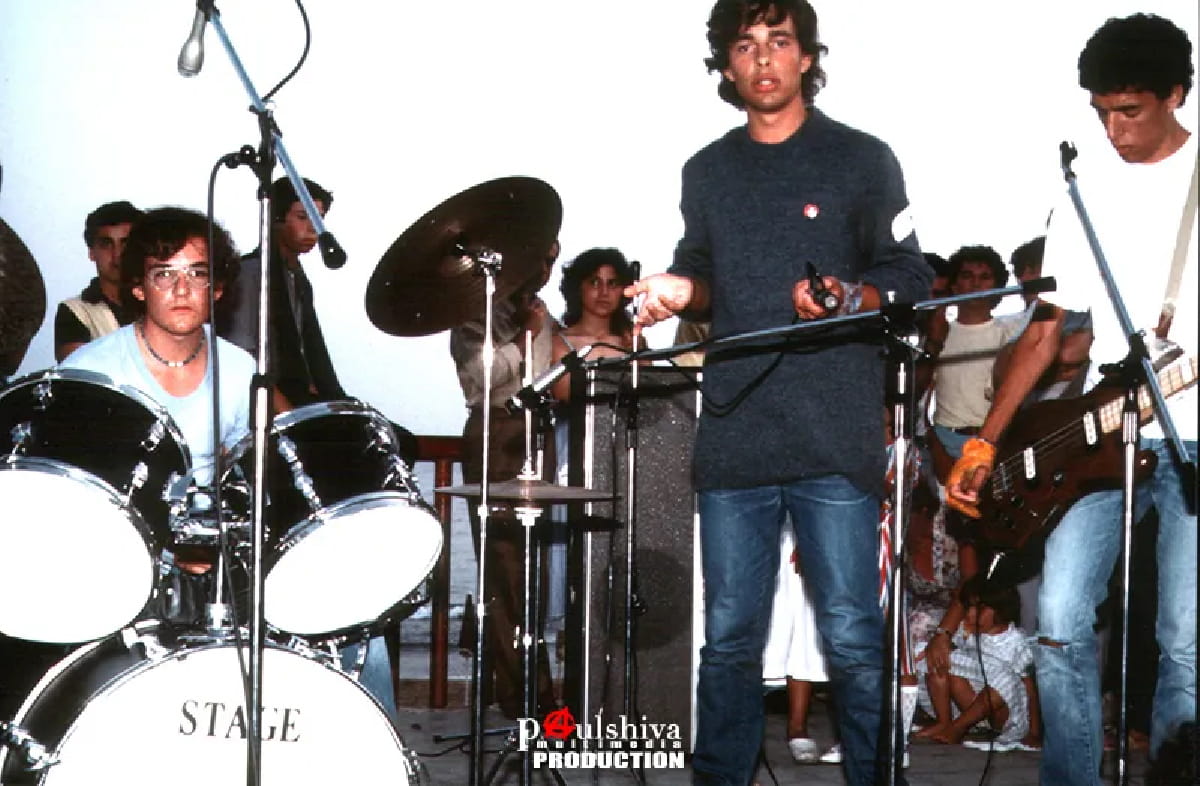

Palmacci, also known as Paul Shiva, grew up inside the Italian punk and post-punk underground. He played in a series of short-lived, obscure bands—Negative Existence, No Existence, The Bathroom Flowers (also known as Fiori del Cesso), and Hard Score Rage—operating on the fringes of scenes shaped by punk-77, no wave, dark, and industrial mutations. Looking back, he describes himself less as a musician and more as an “agitator”, a word that still fits how he approaches culture today.

Around two years ago, he began what he calls an “anthropogenetic rewind”. Capit Mundi?—a Latin-flavored question that roughly translates to “do you understand the world?”—is his attempt to dissect how his generation arrived where it is now. Fanzinet is a central part of that broader framework. The work is openly historical and political without turning into a slogan. It starts from a blunt assumption: we are the result of our own paths, and if we do not examine every step—where, how, and why—we have no chance of correcting the next one.

That rewind led him straight back to fanzines.

In the 1980s, Italian punk fanzines functioned as infrastructure.

Each one had a physical address—street, number, city—that worked much like an IP address today. Palmacci describes every zine as a “link” in a fully analog network. “Even with basic and essential protocols like phone tokens and stamps,” he explains, “that network was every bit as effective as today’s web.” In some ways, he considers it more effective, precisely because it was slow, material, and demanding.

You waited days for replies.

Long-distance phone calls were rare because they were expensive. That friction forced people into physical space—venues, squats, rehearsal rooms, streets. If you wanted information, you had to show up. If you wanted connection, you had to participate. For Palmacci, that material constraint created a density of relationships that digital speed has gradually thinned out.

Within this context, fanzines were not decorative artifacts but working tools. Handwritten or typewritten, cut-and-pasted, mimeographed or photocopied, they were amateur by definition—what would now be labeled lo-fi. Yet they enabled what philosopher Pierre Lévy would later call “collective creativity”: scenes talking to scenes, ideas mutating across cities and countries, aesthetics crossing into politics and back again.

Palmacci’s approach to Fanzinet is deliberately “from below”. First, because he was there, operating at the most basic underground level, with bands that never crossed into visibility. Second, because he sees this flood of self-productions as an “amniotic fluid” without which nothing—not even what later surfaced into the mainstream—could have existed.

The result is a systematic, organic mapping of Italian punk fanzines from the 1980s, published through the Capit Mundi? blog. What sets Fanzinet apart is not only its scale but its refusal to canonize. Palmacci is not selecting highlights or building a greatest-hits archive. He documents everything he can find, treating obscurity as structural, not incidental.

At present, Fanzinet includes 695 mapped fanzines.

Of these, 676 complete issues are available in full, free to read or download as PDFs, in line with the DIY spirit that produced them.

The project includes an interactive graphic map and an alphabetical list designed to improve usability. Palmacci actively invites tips, corrections, documents, and suggestions, framing the archive as something that must remain open-ended to stay truthful.

For him, the value of the project is not limited to preservation. The work itself has forced him to exhume relationships that had been dormant for decades—between himself and former protagonists, and among those people as a result of renewed contact. Boxes in basements have been reopened. Old correspondences resumed. Documents never meant to last have been pulled back into circulation.

Palmacci is explicit about what he sees as the damage caused by dematerialized communication. He notes that as the web evolved—from 1.0 through the current 3.0—connections became faster and more global, while physical contact steadily declined. Concepts such as democracy, freedom, and equality, once tied to real struggle and tangible risk, are now often treated with suspicion or emptied of meaning. He does not consider this accidental. Referencing John Sinclair, he contrasts the unifying power of printed countercultural media with what he describes as a digitally engineered “divide et impera”.

For Palmacci, memory is not neutral. Losing it means erasing identities, dulling critical capacity, and weakening the desire for freedom—outcomes that serve any form of power interested in reproducing itself. In that sense, Fanzinet is not a nostalgic archive but a tool for continuity.

The fanzine mapping is only one section of the wider Capit Mundi? project. The next step, scheduled for spring 2026, is the release of a vinyl compilation titled “No Capitulation”, bundled with a new fanzine called “Capitzine?”. The compilation will feature recordings by extremely obscure Italian bands, likely from the 1980s—material Palmacci encountered through the same network of revived contacts, so marginal it feels as if it surfaced from a parallel dimension.

He frames this as a continuation. The aim is modest: to generate “some small new state of agitation”, to let a few drafts of the old DIY spirit circulate again, and to inject a minimal amount of disorder into what he sees as today’s cultural and ideological desert. If that process manages to reignite even a trace of critical awareness in how digital media is consumed, he considers the effort worthwhile.

Paolo Palmacci, aka Paul Shiva, signs off without slogans. Fanzinet remains open, unfinished, and deliberately porous—much like the scenes it documents.