The evocative notes of “Fresques sur les parois secrètes du crâne” are set to reverberate once again, as Cheval de Frise unveils its second album on vinyl and cassette, two decades post its original CD debut. It’s intriguing how time has only intensified its allure, making it more cryptic and intriguing, as if the album cloaks itself in an enigma that’s challenging to decipher.

When you first delve into this audacious creation, you are met with a whirlwind of melodies that seem to defy categorization.

The traditional markers of math-rock or post-genres fade away, leaving listeners in a labyrinth of sound. What were Thomas Bonvalet and Vincent Beysselance thinking when they crafted this?

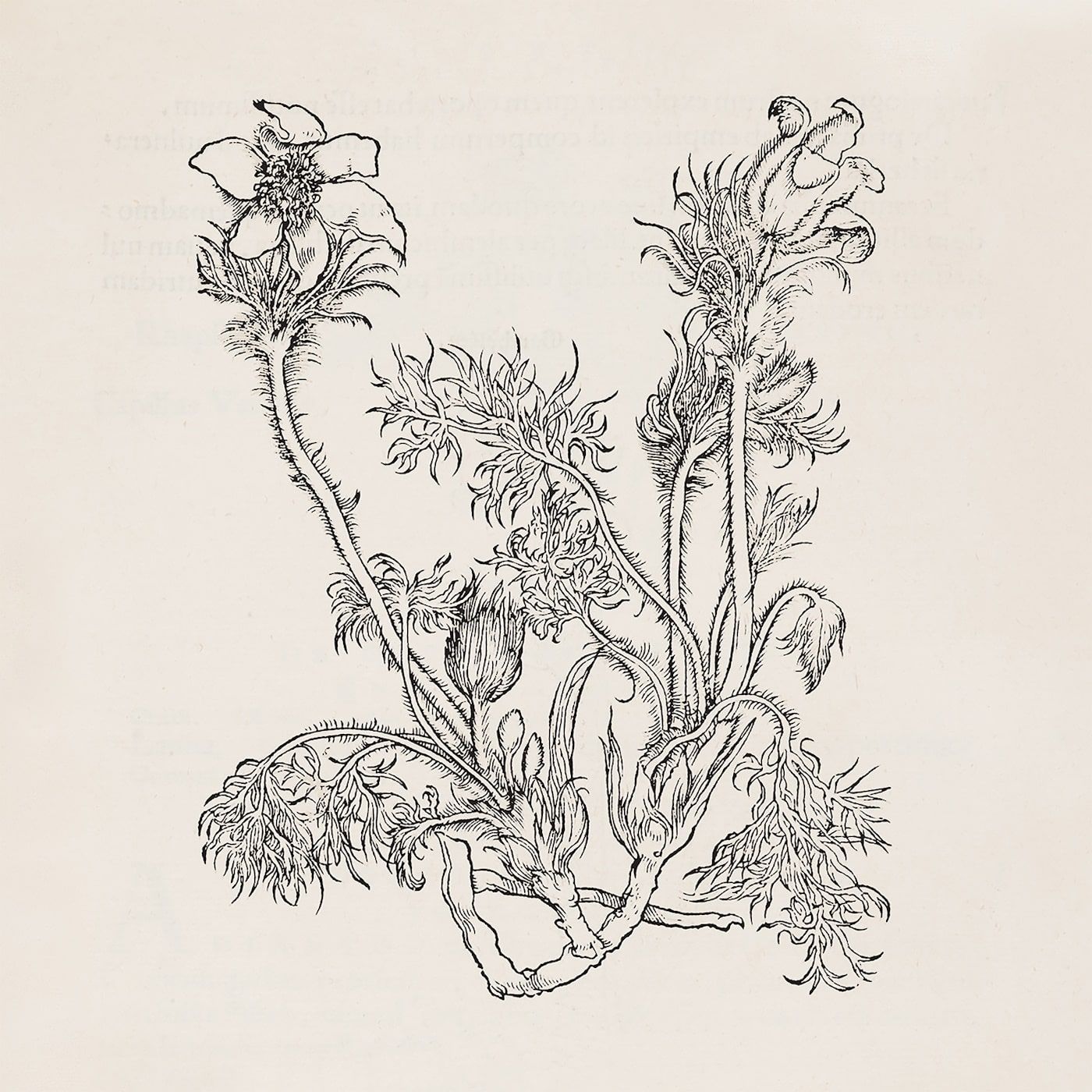

Picture two youthful souls, possibly malnourished but burning with fervor, recently noticed by the underground elite. Their world is a cacophony of instrumental musings, poetic daydreams, and an eclectic mix of inspirations ranging from post-hardcore bands to Renaissance botanical engravings.

This album feels like a journey through a sonic gallery, where influences from bands they admire are transformed and reimagined.

The duo’s love for drums is evident; they discuss, reimagine, and glorify the instrument, crafting rhythms that echo through your very being.

Even the guitar work by Bonvalet resonates with a rhythmic pulse, drawing listeners into a unique soundscape.

“Fresques sur les parois secrètes du crâne” is a testament to Cheval de frise’s ability to conjure up a world that feels both familiar and alien.

The album, slated for release on November 17, 2023, through New York City’s Computer Students™ label, is more than just music.

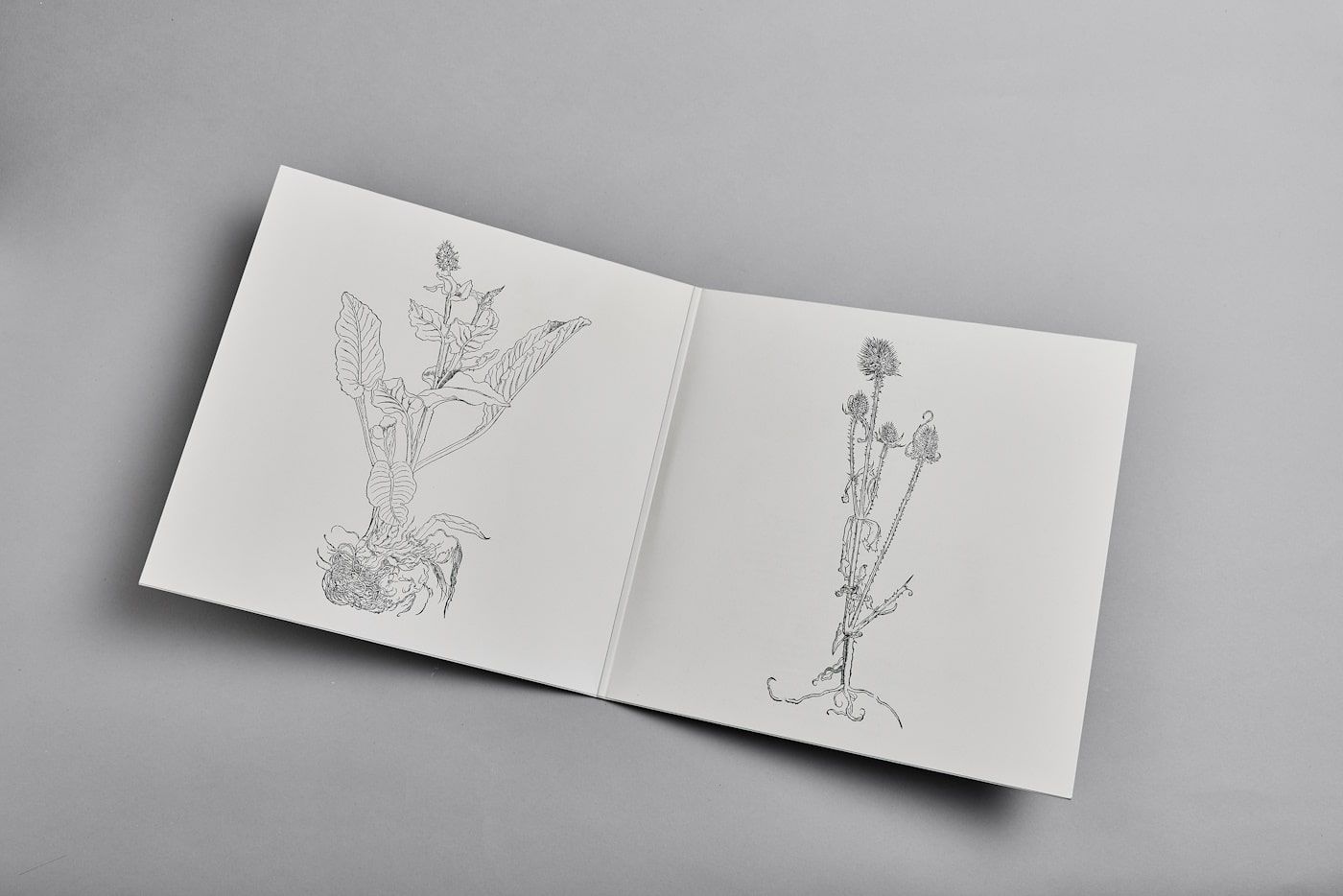

The white vinyl comes adorned with illustrations from Otto Brunfels’ “Herbarum Vivae Eicones” (1532), provided by the University of Padova’s botanical garden.

A 12-page booklet accompanies it, featuring photos captured by Thomas Bonvalet, offering a glimpse into the duo’s world.

But what truly sets this reissue apart is the meticulous remastering by Carl Saff in Chicago, ensuring that each of the 10 tracks feels fresh yet nostalgic.

And while much can be said about Cheval de frise and their uncanny ability to evoke myriad emotions, one thing is clear: their music remains as elusive and captivating as ever.

And for those yearning to dive deeper into the minds behind this masterpiece, stay tuned for our in-depth interview with the band, where they shed light on the inspirations and stories behind “Fresques sur les parois secrètes du crâne”. But for now, let the mystery linger, and let the music speak.

The title “Fresques sur les parois secrètes du crâne” carries a poetic weight. Can you shed some light on the inspiration or story behind this particular choice of title?

The title is inspired by a sentence in the first pages of the first book, half novel, half poem, by the American writer William Goyen, The House of Breath.

Your music on this album is described as mysterious, elusive, and even transfigured. What were the primary emotions or experiences you aimed to encapsulate during its production?

There was an urgency and an evidence in the composition of our first untitled album and its relative success was a surprise. A second album is often a delicate ordeal, and we could have benefited from this initial momentum. To consolidate, cement and refine this music without destabilising ourselves. But it was a much more sinuous path that presented itself.

At the time, I think I felt the need to develop things that were more complex in their evocations, and Vincent ( Beysselance, drummer of CDF) was also pushing his playing towards things that were more complex and less rock. Doubt, questioning. The general mood was darker and more worried, but there was also a taste for the grotesque and the fantastic that pushed us to develop strange forms, this act is almost playful and implies a desire to surpass ourselves. It was a joy and an exhilaration to see things materialise that seemed (naively) unheard of, at least to us. There’s a real taste for singular objects.

The New York Times describes your work as unresolved riffs interrupted with flamenco runs. Where did the inclination to integrate flamenco elements come from, given that the genre is not often combined with heavier sounds?

The reference to flamenco is purely accidental; we didn’t have this musical culture and weren’t even aware that we were evoking it. I think it has a lot to do with the choice of instrument, the classical guitar. When I was a teenager, most of my culture was linked to punk, hardcore and all the music that came out of that in the 80s and 90s. Gastr Del Sol, while being in some ways in that filiation, opened me up to a whole new range of sounds and forms, and the acoustic guitar was an important and attractive part of that. I also really liked Swell’s ’41’ album.

I could have bought a steel-string acoustic guitar like those bands, but I had a nylon-string classical guitar at home. It was just there without being explored, I didn’t really know how to play it, my instrument was the fretless electric bass, the first rehearsals of the band were actually on bass, but feeling limited I tried to amplify this old guitar.

Played in this very energetic way, the classical guitar can evoke something completely different from rock, and this went beyond me.

Given that “Fresques sur les Parois Secrètes du Crâne” was initially released on CD and now sees a vinyl and cassette tape reissue, do you feel that the format might influence or change the listener’s experience of the album?

No, I don’t think so and I don’t want it to be so. This music doesn’t depend on the nature of its format or the evocations of its artwork. I’m attached to the visual aspect of the object, but even if there are obvious correlations, they take place in parallel, in another dimension as it were, on another plane.

You’ve been compared to a myriad of genres, from math-rock to “post-everything”, yet you seem to defy these labels. How would you describe your own sound, and do you believe it’s essential for an artist to fit into a genre?

I find the notion of genre interesting retrospectively, to name the emergence of new forms in the evolution of music and to determine their filiations.

I didn’t felt we belonged to a defined, precise genre. But there is a zeitgeist, there are trends, and despite some more or less intentional singularities, we couldn’t totally escape them. All the same, I felt, and this became more pronounced over time, the need to determine my own territory, a vital space, a refuge.

There’s also the need for transformation and rupture and the discovery of new fields of possibility. This makes the notion of genre less relevant, even though there are obviously filiations, evocations and references.

Were there any particular artists or albums you were listening to during the creation of “Fresques” that helped shape its sound?

I mentioned Gastr Del Sol a bit earlier, I was still very attentive to what David Grubbs was doing and I’d love his solo records from those years …I must have listened a lot to A Spectrum Between, which came out during the “Fresques” composition period.

I was a big fan of Craw and I’d managed to convert Vincent to that music as well, to a certain extent. I don’t think there’s been a day in all the years of Cheval de frise activity that I haven’t listened to a Craw record, I love them all but I think their album Map Monitor Surge was the one that was most present during the conception of these tracks, a very strong influence even if on the surface we’re very far from that sound.

Your early days involved grueling concerts and intensive listening sessions. Can you share an anecdote or pivotal moment from those times that contributed significantly to shaping the album?

I remember a climate, routines, the damp, unhealthy cellars and basements of Bordeaux where we spent most of our lives, whether it was the endless hours of rehearsal or the concerts we did, organised or went to see.

Then there were the hours in the van, the absurd distances. I also drove bands on tour, in addition to our tours. So I spent a lot of time at the wheel with the hypnotic roar of the engine.

Vincent had a more balanced life than I did, he was a student and did sport. My life was exclusively devoted to music, in the broadest sense of the word… because I was also responsible for putting together all our tours, we didn’t have an agent, I did everything myself. I can’t think of a single decisive event, but there were some decisive encounters during those years, some strong friendships and musical encounters that were very important for what happened next. I’m thinking in particular of Gorge Trio, or Radikal Satan…

The artwork for the vinyl reissue features illustrations from Otto Brunfels’ “Herbarum Vivae Eicones’ (1532). What is the connection or resonance between this choice of artwork and the music contained within the album?

There are no deliberate links, but things have a natural coherence, a rhizomes-like subterranean unity.

A choice of notes, a choice of rhythms, a choice of timbres, a choice of images and words, all emanating from the same subjectivity in a given timeframe, things are one.

The photos by Thomas Bonvalet, buried in 2007 and unearthed in 2017, seem to have a deep narrative. Can you take us through the journey of these photos and why they were chosen for this reissue?

I had a large collection of analogue photos covering more than ten years of my life, ranging from personal photos to essays for record sleeves and more modest artistic things.

In 2007 I moved into a small cabin on the edge of a pond, in a forest called ‘La Double’. I didn’t have any storage space, I also needed to wipe the slate clean and all those photos were weighing on me a bit, but I didn’t want to destroy them. I decided to put them in what I thought was a perfectly airtight box and bury it in the forest. Ten years later, I wanted to see those photos again.

When I dug them up, I discovered that roots had opened up the box, allowing water to penetrate. The photos were bathed in a blackish soup, they were all altered, decomposed… In the middle of all these photos, there was a series of still lifes that I had done for tests for the “Fresques” cover, only one of which we had kept at the time for the inside of the booklet. We brought together a number of them in this altered form for the booklet of this re-edition.

How did the collaboration with Computer Students come about? What was the experience of working with a New York City label?

Things happened very naturally. I’ve known Julien Fernandez (label boss) for many years. His band Chevreuil was formed the same year as Cheval de frise (1998), we’ve shared stages on several occasions and we’ve been supported by the same labels (Ruminance and Sickroom).

Vincent also collaborated with him on the debut album of his intrumental metal band Tormenta, released on Julien’s ex-label Africantape in 2011. I was very happy to receive his proposal for the reissues and very happy to work with him on these objects.

The packaging from Computer Students comes as an iconic and laboratory-like work of art. How does this aesthetic resonate with the essence of Cheval de frise, and what prompted this unique presentation?

Only the outer aluminium packaging is a kind of aesthetic charter for the label. As for the rest, Julien has not only been very respectful of the original material, but has done everything to optimise and perfect things to make the most beautiful objects possible. He has done a remarkable job.

Are there any recent releases that have impressed you, especially in terms of visual presentation and packaging? Can you recommend some for us to check out?

I don’t listen to music any more or very rarely and I haven’t bought a record for many years. I’ve been suffering from Pain Hyperacusis with Tonic Tensor Tympani Syndrome for more than 6 years, the disease has been evolutive, it has deteriorated considerably in the last two years and I can no longer play music.

Listening to it, even at low volume, is often uncomfortable and unpleasant.

But music is always present in me, I have a kind of inner jukebox, I can go through whole pieces, whole albums from memory and the pleasure is quite similar to listening.

Given the reissue, how do you feel about the current state of the Bordeaux music scene? How has it evolved since your initial release?

I don’t know anything about the current scene in Bordeaux, I left in 2005. And generally speaking I’m getting further and further away from the music scene.

Vincent also left Bordeaux for Paris in 2004 for professional reasons.

You’re described as having a “hair-raising sense of vituperation”. How do you maintain such intensity and passion over the years, especially as the musical landscape evolves?

The band split up in 2004 and that must have been the last rock project I was involved in. I made a lot of music after that, in a lot of different projects (l’ocelle mare, Powerdove, Radikal Satan, Arlt, among others) but it was all very far removed, formally, from Cheval de frise. And as I said, I had to end my career two years ago.

Vincent remained active until 2012 with his metal band Tormenta. He now plays cello in an amateur classical orchestra, and continues to play drums in a few informal projects.

Finally, looking back, is there something you wish you knew when you first started out? Any advice for young artists embarking on their own sonic explorations?

I could have said that I would have liked to take better care of my ears and my health in general… but in the end I have no regrets and no recommendations, there is only passion and necessity that expresses itself in these young years and we must not curb this momentum.

I’m not sure that moderation and caution produce the most exhilarating works!