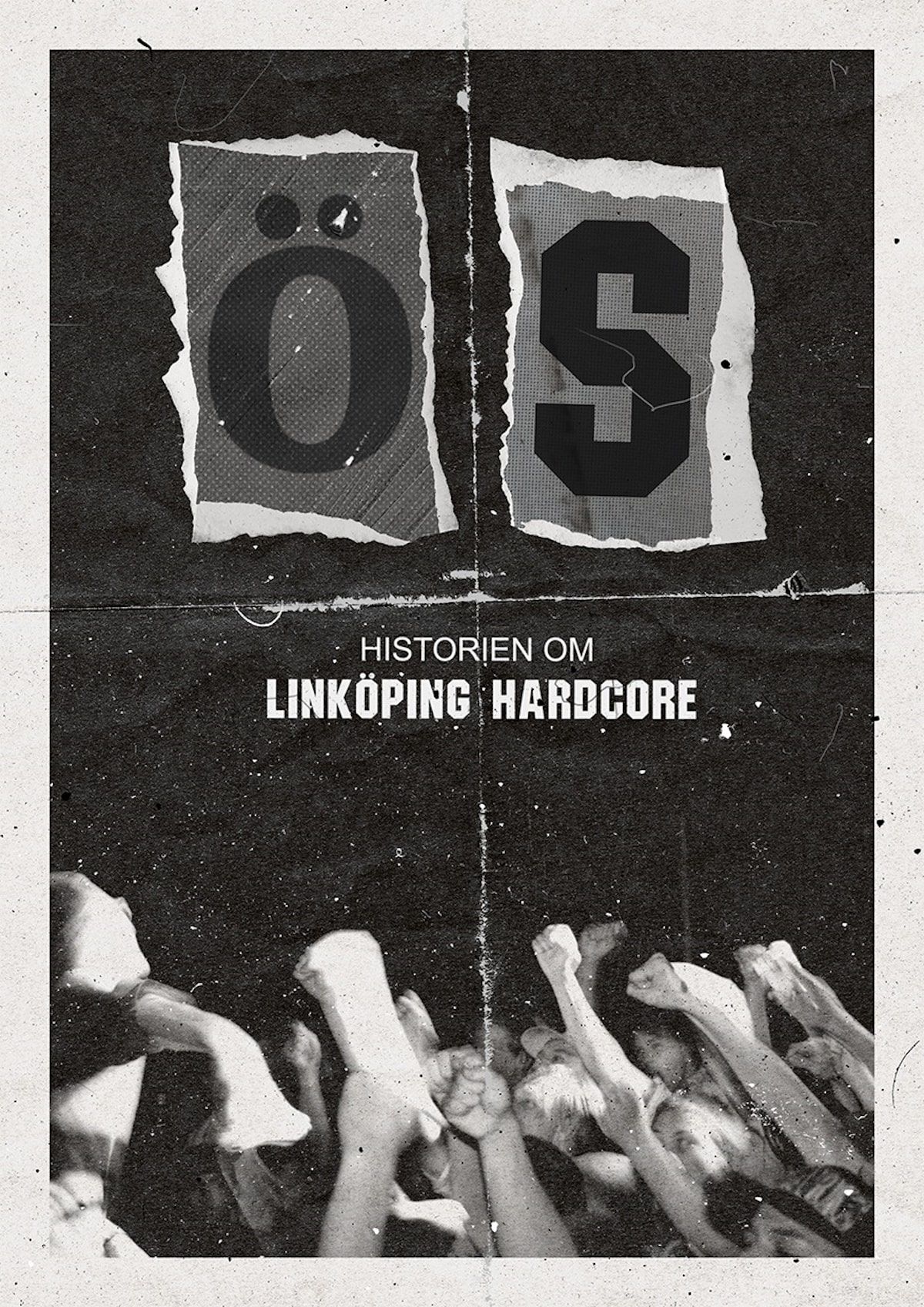

It started as a passing idea between old friends from the scene — Anders Carlborg and Errol Tanriverdi from First in Line — talking about how no one had ever tied together the wild, messy history of Linköping Hardcore. Two decades later, that idea became “ÖS – The Story of LKPG Hardcore,” a film that pulls together decades of noise, sweat, and stubborn heart.

The project took shape in 2021, when Carlborg launched a Facebook group called Linköping Hardcore Doc, asking people across Sweden to dig up old photos, tapes, and flyers. Within a year, he had enough to run a successful crowdfunding campaign, and filming kicked off soon after. The movie premiered in May 2024 at Skylten — the city’s legendary DIY venue and the beating heart of this story.

Watch it at lkpghc.com!

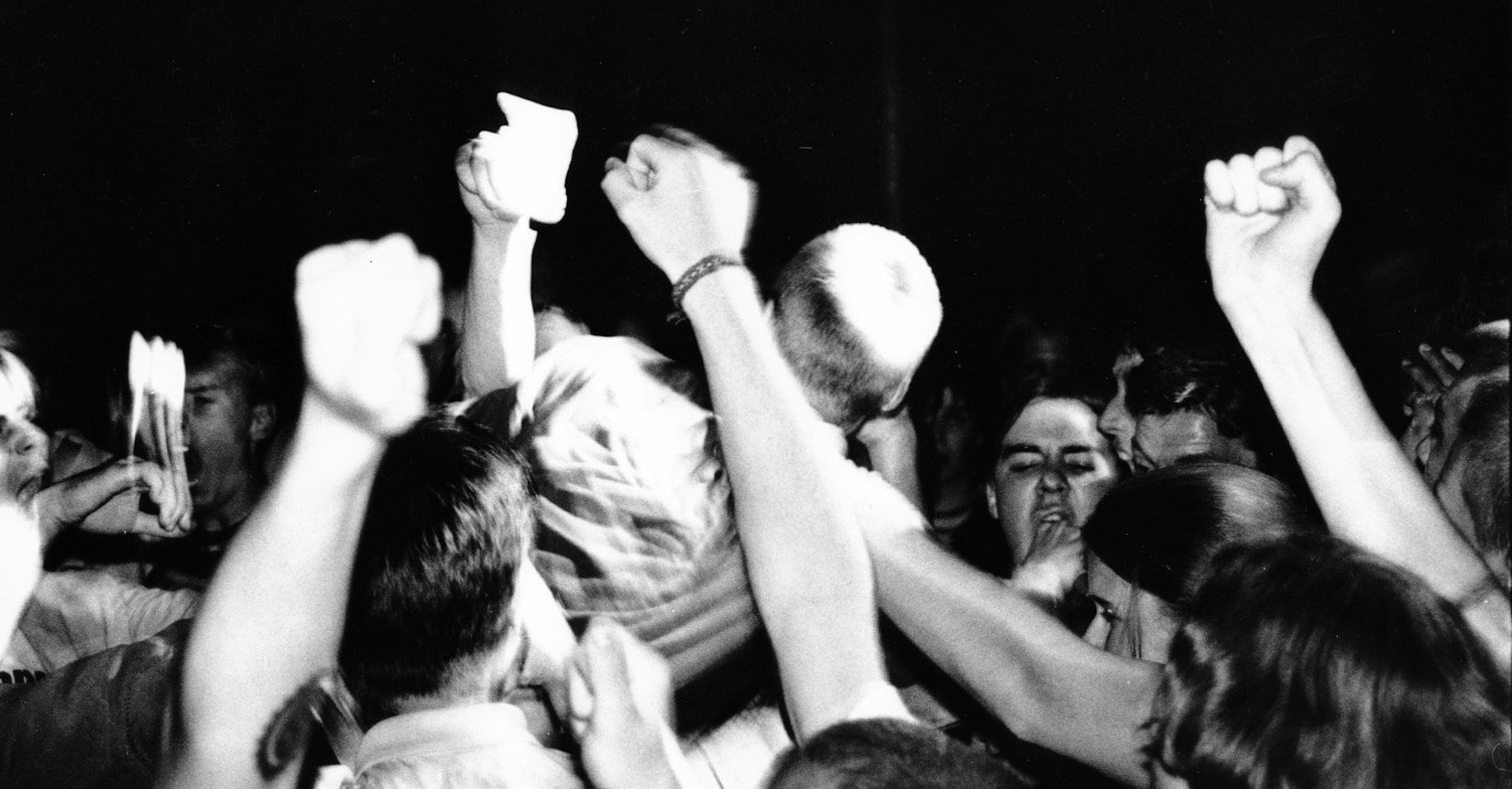

Skylten was more than a concert space. It was a social experiment that worked — a run-down factory handed over to the youth that became one of Sweden’s most important breeding grounds for underground music. “We were honestly pretty lucky that the city let us be as free as we were,” Carlborg says. Hardcore took over, driven by the most dedicated people, and Linköping soon stood shoulder to shoulder with Umeå and Vänersborg as a key hub in the 1990s.

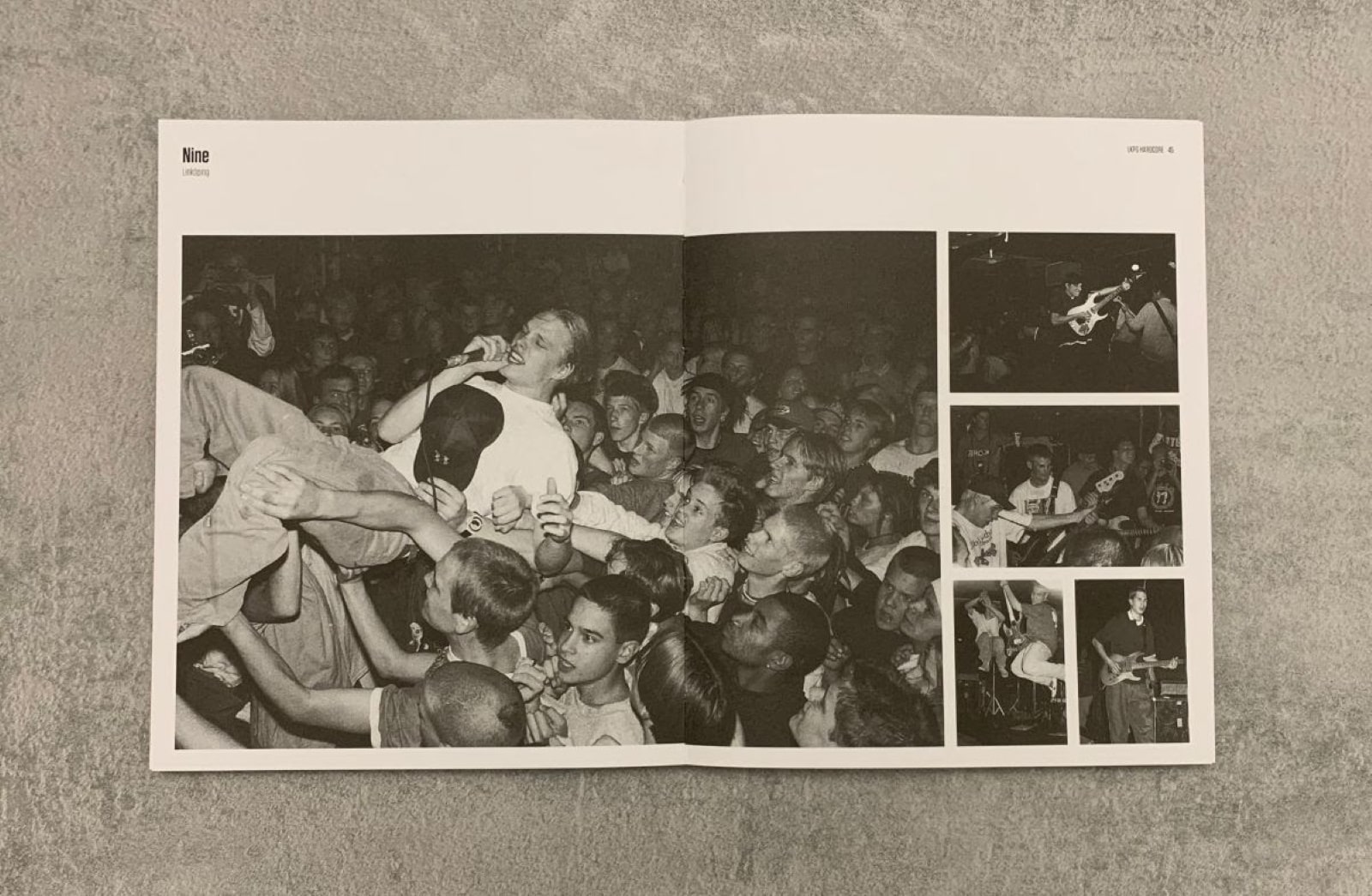

While digging through the archives, Carlborg found long-lost gems — 8mm footage from Kurt i kuvös in 1981, early Raped Teenagers and Nine shows, and the last radio interview with Benjamin Vallé. Not everything made it into the final cut, but the film still captures what made this scene different — the sense of self-built purpose and the handoff between generations. “Each one needs to help the next carry the torch,” he says.

The story ends where it began — at Skylten, with Dunderjorden and Dunderfest keeping the pulse alive. New bands like Viggen and Lost Faith are picking it up, while veterans still show up and help. Since the premiere, Carlborg keeps getting new material sent his way — “People are still finding VHS tapes and photos I’ve never seen before,” he says.

“ÖS – The Story of LKPG Hardcore” is a great proof that the noise never really stopped. As Carlborg recalls, “After one screening, a young punk band told me the film inspired them to write a hardcore song dedicated to me. That’s the biggest compliment I could ever hope for.”

Read the full interview below — we talk about the film’s roots, the ghosts of Skylten, and the new blood shaping Sweden’s hardcore today.

How did you first catch the spark for this project — was it a memory, an artifact, or just the sense that nobody had yet tied all those scattered stories together?

The idea for the film was born back in the early 2000s, when I was chatting with Errol Tanriverdi (vocalist in First in Line) about trying to document what we had experienced during our time in the Linköping hardcore scene during the 80s and 90s.

Unfortunately, the idea was shelved when I moved to Stockholm and began a career as a film and TV editor. But the thought stayed with me over the years. Then in 2020, Kristofer Pasanen released his photo book Where We Belonged, all about Linköping Hardcore. When I saw the huge interest it sparked, I realized the time was right to revisit the idea.

So, in spring 2021, I started a Facebook group to try to track down people who might have photos, flyers, VHS tapes, records—anything from back in the day. Over the course of a year, I collected loads of amazing material. In spring 2022, I launched a crowdfunding campaign—and to my surprise, it was a huge success. The next two years were spent filming, and by spring 2024, the film was finally finished.

When you started digging through old posters, demo tapes, VHS rips, did anything hit you harder than expected — like some detail that suddenly opened up the whole atmosphere of a certain year or show?

I found so much cool stuff, but one of the absolute highlights was an 8mm film of the band Kurt i kuvös, given to me by drummer Staffan Fagerberg. I honestly never thought I’d find moving footage from as early as 1981!

There were plenty of other gems too—like video footage of Raped Teenagers, Identity, Nine, and Surfface (who later became Outlast). I was also incredibly grateful to get access to the last radio interview ever done with Benjamin Vallé (from Nine, Viagra Boys, etc.). It allowed me to tell his story in a heartfelt and respectful way.

Skylten almost feels like a character in the film. Did you discover things about that place that even longtime locals didn’t know, stories hidden in the walls that surprised you?

I may not have uncovered any wild new secrets about Skylten, but digging into how the concert activities first started in the 80s was fascinating. Many of us who entered the scene in the 90s didn’t really know that early history—and it turns out it had a huge impact on what we later experienced during the second wave of hardcore.

I also think a lot of people might have missed the fact that Dave Grohl was there with Scream in 1988, and getting photographer Anton H Le Clerq to dig up the original negatives was a fun thing to be part of.

There’s a proud tradition in Sweden of municipalities handing over spaces to the youth, but Skylten’s DIY spirit seems to have gone further, shaping not just concerts but a whole identity. How did you balance that civic experiment with the raw chaos of hardcore?

We were honestly pretty lucky that the city let us be as free as we were at Skylten. The building hosted all kinds of bands—pop, rock, metal, hip-hop—you name it. It was a melting pot of creative energy. But hardcore stood out, partly because it attracted the most dedicated and driven people, and that’s probably why it became the dominant sound. That said, there was a real diversity on stage, especially early on, before things became a bit more genre-split.

When you think about Linköping in the 80s and 90s, what made it explode the way it did while other Swedish cities maybe didn’t reach that same fever pitch? Was it luck, geography, a handful of obsessed people, or something else in the water?

I think one of the key reasons was the passion and drive of certain people. There were hardcore enthusiasts in the 80s who laid a solid foundation—not just in Linköping, but in the surrounding areas too. That inspired a new generation who picked up the torch in the 90s.

Maybe some of it came down to timing and luck. But Skylten was also just the kind of place that drew in young people who maybe wouldn’t have gone to concerts otherwise. I still remember how cool and mysterious it felt the first time I went there. The band I played in (Backside)—like so many others—dreamed of rehearsing at Skylten. It was the place to be if you wanted to escape the boring, boxed-in everyday life in Linköping.

Hardcore history in Sweden often circles around Stockholm, Umeå, and Gothenburg — scenes with their own myths. How did Linköping’s story intersect or clash with those bigger narratives?

I’m not sure how it was during the 80s when it comes to the leading cities but I’d say Umeå, Vänersborg, and Linköping were the big three during the 90s. Sure, you could play gigs in pretty much any small town, but those three cities really stood out. There was always a bit of friendly rivalry between scenes, and you always made sure to represent your hometown when you played.

Was Linköping as important as Umeå or Vänersborg? I think so. Umeå maybe had bigger bands and stronger media presence, but if you ask people which bands stood out in 90s Swedish hardcore, you’ll probably hear Nine, Outlast, and Section 8. That says a lot about the impact of Linköping Hardcore.

Today cities like Stockholm, Göteborg and Malmö are big cities when it comes to hardcore but Linköping also has a thriving scene.

I imagine while editing, you had to make painful choices — entire anecdotes, characters, or tangents that didn’t make the final cut. Which parts of the story do you still carry around in your head, wishing people could see them?

Of course, not every story made it into the film. The first rough cut was well over two hours! One example that had to go was Meat Eaters and their legendary demo tape Give Me a Hamburger for Half the Price from 1984. Or Raped Teenagers’ chaotic (and slightly disastrous) European tour.

I also filmed an entire segment about veganism and the classic “punk stew” that was always served at gigs. There are tons of stories like that, but cutting some of them made the overall film stronger. Who knows—maybe I’ll release some deleted scenes someday.

On a personal level, was there a moment in the making of the film when you felt like, “this is why I’m doing it” — like it all clicked into place and the community made sense as one thread?

From the very beginning, the support was amazing and it made me sure of why I was doing it. When I launched the Facebook group, I instantly felt this huge wave of encouragement from the community. That kept me going through all the hard work. I never doubted the project, even when it got tough.

The documentary ends in the present, with Skylten still alive and the Dunderjorden collective fueling new generations. How did you want to show that continuity without just leaning on nostalgia?

When I started filming in 2022, I knew that the first ever Dunderfest was happening—and of course, I had to capture that. It ended up being the very first thing we filmed. Since the movie is told chronologically, it felt natural to save that part for the end. It was a great way to show that hardcore is still alive and kicking at Skylten today.

Scenes like this are fragile — they come and go depending on who’s willing to put in the hours. What did you learn about sustainability in hardcore culture while talking to both veterans and younger kids?

It’s incredibly important that each generation helps the next one carry the torch. That happened naturally between the 80s and 90s, but around the early 2000s, the momentum faded. Maybe the next generation just wasn’t as hungry—or maybe too many key people left the scene and moved from Linköping. The renovation of Skylten and the general dip in hardcore interest in Sweden also played a role. But yeah, passing down that legacy really matters. If that makes sense?

Sure thing! I’m curious about your view on Dunderfest — does it feel like a natural extension of the old days, or more like a reinvention, built by kids who carry the same fire but in a completely different era?

Dunderfest is now run by people from the 90s scene and has become a fantastic platform for young, music-loving newcomers. The first year didn’t attract many young visitors, but that’s changed. I attended the 2025 edition this September and was blown away by how many young people were there—and even more so by how many are now starting bands and getting involved in organizing the fest.

Two new promising bands from Linköping worth checking out: Viggen and Lost Faith.

When you were traveling with the film across Swedish cinemas, what was the wildest or most unexpected audience reaction you got?

One of the most touching moments came after a screening in Visby. A few months later, I played at a festival in the south of Sweden with my band Knifven. That same evening, a young local punk band called BOT from Visby performed. They told the crowd they’d loved the film—and that it had inspired them to write a hardcore song, which they dedicated to me. That’s honestly the biggest compliment I could ever hope for: knowing the film inspired a new generation to make music.

The standing ovations at the Skylten premiere were incredibly emotional too—but really, every screening has felt very special.

Since the premiere, have new boxes of tapes, flyers, or private stories suddenly appeared on your doorstep, people saying “hey, I’ve got something you need to see”?

People are still reaching out with materials. Just a few weeks ago, Johan Lindqvist (from Nine) contacted me because he found a VHS tape with a filmed Nine gig I didn’t even know existed. So yeah, there might be a future project to create some sort of archive with everything I’ve collected… but when and how? That’s still up in the air.

Looking at the Swedish underground right now, who do you think is carrying the torch in interesting ways — bands, collectives, maybe even unexpected corners of Östergötland or elsewhere?

I already mentioned Viggen and Lost Faith—but First in Line is a classic band that actually started way back in the late 80s. Moralpanik, with David Andersson from Identity on vocals, is another great one from Östergötland.

If I keep going with bands that has local connection, I have to include Nowheres, Alarm, and Vidro. And of course, a little self-promo: my own band Knifven released the album Linköping! in 2024—right when the film premiered—consisting of punk and hardcore covers from Linköping bands.

You spent years piecing together the past, but I wonder if working on the film also shifted how you see the present — has it changed the way you experience a hardcore show today?

Not really—but it did give me a whole new level of respect for what the bands in the 80s built. That was something I didn’t know much about when I started the film, but I’m so glad I got to learn it along the way.

And just for fun — if you could sneak one scene from Swedish hardcore history into the documentary that was never captured on tape, something you wish a camera had been rolling for, what would that be?

There’s a local myth that Skylten is haunted. Several people who spent the night there back in the 90s claim they saw—or heard—something strange.

We got to use the space for free over a few weekends and when we were filming interviews there something spooky actually happened. The place was totally empty and just as we were about to start an interview with David Andersson, the café’s speaker system suddenly turned on and started playing music—completely on its own. Maybe we had a chance to catch the ghost on film… now that would have been epic.