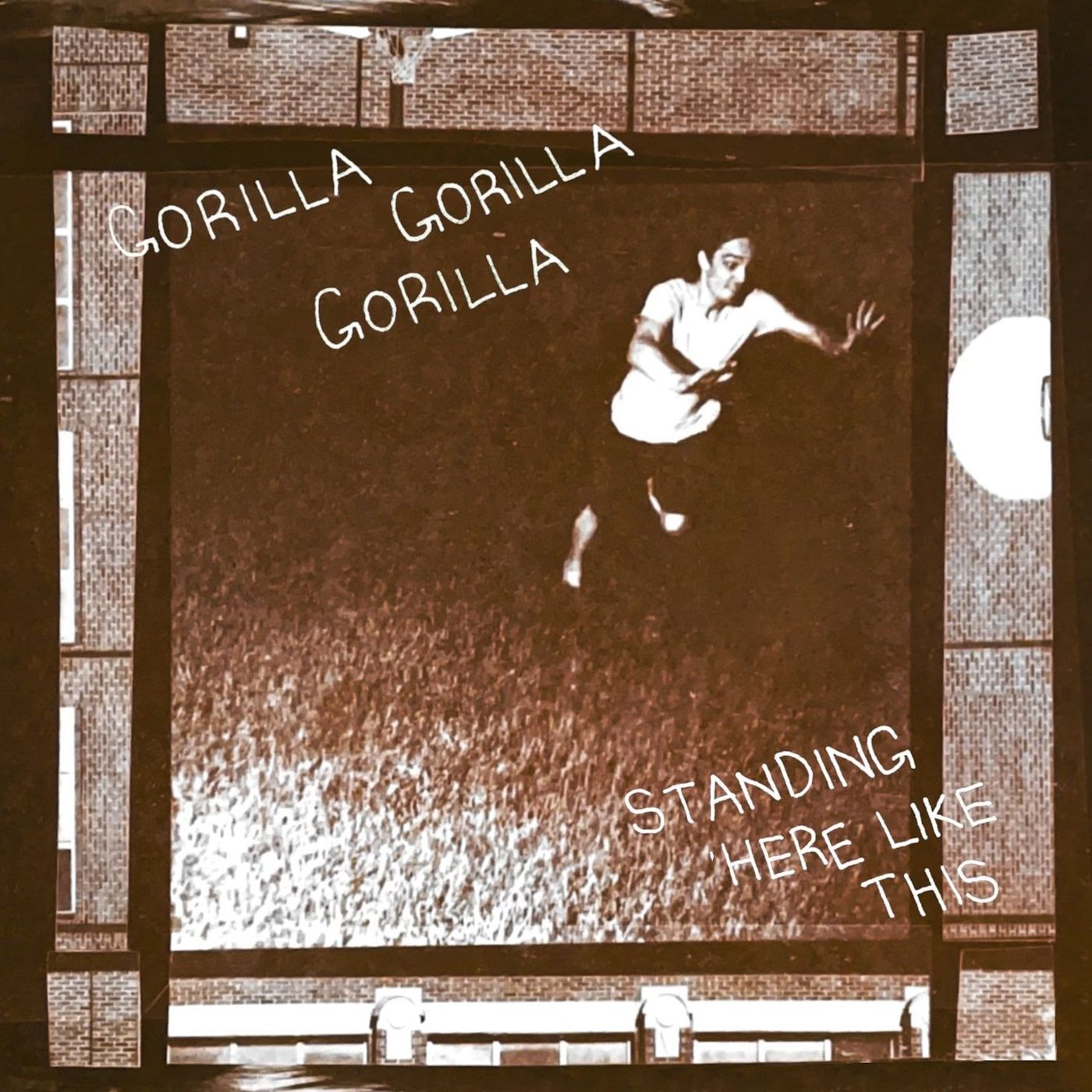

Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla, a band emerging from the depths of the emo post hardcore scene, notably half comprised of members from the band Faced Out, have recently released their debut EP, “Standing Here Like This.” The album represents a sonic journey through the abrasive side of the second wave emo revival, occasionally teetering on the edge of screamo.

But it’s more than just an album; it’s a manifesto, a reflection of the zillennial experience in a world shaped by late-stage capitalism and a unique brand of melancholic nostalgia.

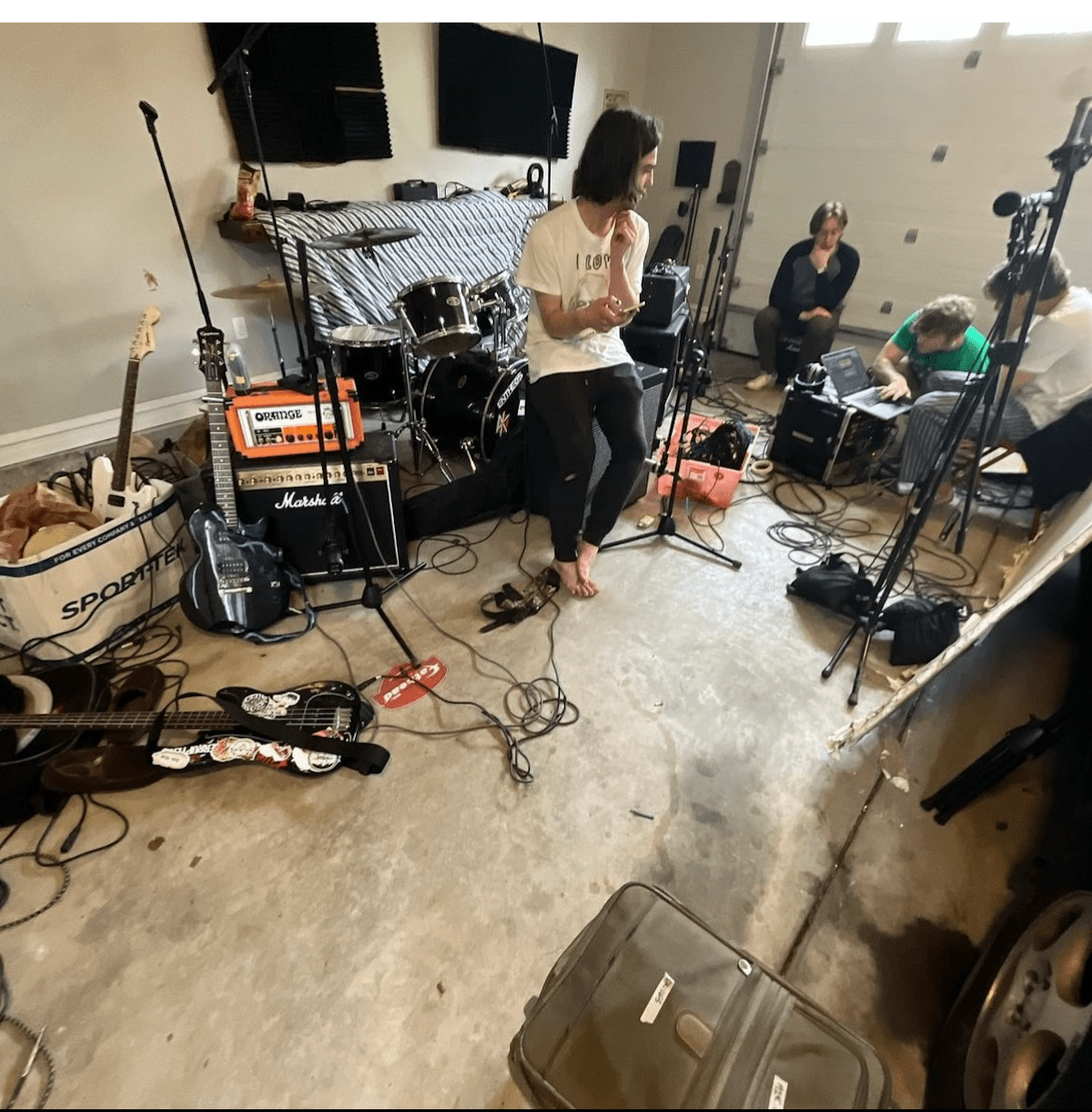

“Standing Here Like This” channels the sound of a cloistered unfinished garage in St. Louis, a space shared with a broken-down car under the May sun, permeated by the influence of copious amounts of weed. It’s an atmosphere that breathes life into their music, drawing inspiration from bands like Snowing, Cap’n Jazz, and Algernon Cadwallader.

An Emo Response to Modern Alienation

The band’s vocalist, deeply rooted in the punk scene, narrates the transition from the overt political stances of basement punk to the more introspective world of emo, marked by personal struggles and experiences.

This shift mirrors the historical trajectory of the emo genre itself, which evolved from a subgenre of punk to a standalone entity. Bands like Cap’n Jazz catalyzed this transformation, making emo a unique reflection of personal hardship rather than broad social criticism.

Marxism and Emo: A Deep Connection

At the core of “Standing Here Like This” is a profound essay by the band, exploring the intersection of emo music with themes of late-stage capitalism and nostalgia. Shared with us exclusively, the essay delves into the inherent melancholy of the emo genre as a response to the alienation experienced in capitalist societies.

The labor that once built communities and fulfilled human creativity has been transformed into monotonous work, leaving a void filled by the longing for a lost youth, a theme pervasive in emo music.

Emo and Political Consciousness

Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla’s music reflects a growing awareness of the connection between emotional alienation and class consciousness within the emo genre. While not overtly revolutionary in its lyrics, the band’s music is a reaction to the material conditions created by capitalism. This perspective is especially relevant in today’s political climate, where the increased persecution of marginalized groups, particularly trans individuals, has revitalized interest in revolutionary ideologies within the emo scene.

Building Forts in the Woods Again

The band’s manifesto concludes with a poignant reflection on their musical journey. From the raw energy of punk to the introspective melodies of emo, the essence remains the same — a quest for meaning and resistance in a capitalist world. As Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla shares their music, they see it as an act of reclaiming the fruits of their labor, a metaphorical return to building forts in the woods, reminding us that “it doesn’t have to be like this.”

“We are Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla. We are communists,” they proclaim, echoing the sentiment of their punk predecessors, yet carving a unique path in the emo landscape. “Standing Here Like This” is not just an EP; it’s a narrative, a commentary, and a voice for a generation caught between the remnants of a past era and the uncertainties of a capitalist future.

The following essay by the emo band Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla reflects on the evolution from punk’s overt political stances to the more introspective emo genre, noting a shift from explicit political songwriting to a focus on personal struggles and emotional alienation.

This change parallels the genre’s own history, where early political discussions in emo music, influenced by bands like Cap’n Jazz, gradually faded, giving way to themes of personal hardship.

The essay further explores the concept of labor alienation in capitalist societies, where work becomes a draining necessity rather than a fulfilling activity, leading to a nostalgic longing for the freedom of youth.

The band’s own music, influenced by this ideological and emotional landscape, seeks to recapture the sense of purpose and community, despite moving away from the direct political activism of their punk roots.

They conclude by affirming their identity as communists, suggesting a hope for a future where music and community can offer an escape from the constraints of capitalism.

Here’s the full letter from Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla:

“We are Pinkville. We are communists.” Jack Levin, the vocalist of the first real band I was in, opened every show with these words. In the world of basement punk, the open and visible adoption of political stances like this is about as commonplace as slipping on spilled PBR or watching a 40-year-old with a receding green mohawk vomit after shotgunning one-too-many FourLokos.

But as I increasingly moved into the seemingly more mature world of basement emo, marked more by spilled IPAs and one-too-many hits of dispensary-purchased weed, the clarity of the connection between musicians and the radical egalitarianism that dominated punk became less-and-less clear. I myself am a communist.

The punk bands that I played in from high school on have generally focused our songwriting on communism and politics at large, but as my late teens wore on and I entered my twenties, I increasingly began to write more about the feelings of loss and melancholy that I have experienced since my youth and less on recitations of Marxist-Leninist theory over 180 BPM power chord riffs.

To some extent, this is not surprising, as the origins of emo stem from a shift in focus towards personal struggles and experiences within the Revolution Summer era DC hardcore scene as its early members grew up. As time went on, bands like Cap’n Jazz made emo a thing unto itself, developing patterns and tropes that would go on to define wave after wave of a scene that could no longer just be defined as a subgenre of punk.

Explicit discussion of politics, initially defocused but not forgotten, faded into the background and by the oft-ridiculed “third wave” had seemingly disappeared completely. Even hardcore, although less so than emo, has begun to increasingly diverge from the political tradition in punk started by bands like The Clash and Stiff Little Fingers in the mid 70’s to focus increasingly on personal hardship rather than on broad social criticism.

In a lot of ways, I see myself growing alongside Guy Picciotto. As the initially sharp anger that grows when we begin work and “real” school in our teens fades, a duller ache begins to set in as we are faced with the prospect of doing this for the rest of our lives. Marx describes this as the product of alienation of our labor.

As humans, we naturally desire a role in building and helping our community through labor. As the transformation to capitalism concentrates decentralized personal property into centrally owned private property, rather than use our labor to help ourselves and those we love, we are forced to sell it in exchange for the goods necessary to keep us alive for another day of doing the same.

Through this process, the labor that is so innate to us as humans is transformed into work, which slowly and methodically beats the living shit out of us until we are too tired and emotionally broken to resist the capitalists.

Much of the content of emo can be interpreted as a response to this process. A nostalgic longing for the freedoms of adolescence and youth were so much a part of Tim Kinsella’s lyricism, that this message has become intertwined with the very fabric of the genre; weaving itself into aesthetics and lyrical content of bands that would go on to be inspired by Cap’n Jazz decades later in the 2010s Emo Revival.

For us, youth is a time when labor was not work. We did not build a fort in the woods for a minimum-wage paycheck, but to create something that approximated, to us, a home. What little labor our small bodies could create went into the tiny communities that flourished in neighborhoods and schools. On Halloween, we would trek miles in search of nourishment, and find ourselves home at the end of the day tired, but able to enjoy in full the fruits of all we had done.

Fear of death, an omnipresent theme in the music of bands such as Marietta arises as our purpose in life fades to a rote recitation of the steps necessary to eat and pay rent. A waste of the beautiful and unique power that we have to consciously give our time and energy to those around us.

But every day we rise and go to jobs or school desiring something more fulfilling from life. In this modern late-stage capitalist landscape “where we’re worn thin, ordered to work in working order”, a large chunk of the US population toil aimlessly at meaningless/unfulfilling middle management jobs that make up > 20% of the workforce, while most others work often-grueling service industry jobs, usually for close to minimum wage.

While many people I meet who operate within the scene tend to have varying degrees of “radical” leftist beliefs, this is often not represented in the lyrical content of a lot of the more recent bands within the genre. In fact, many bands, particularly from the 2010s revival scene seem to espouse pretty blatant liberalism (see Modern Baseball’s Voting Early).

This comfort with the status quo is reasonably in line with the class status of many who engage in the scene: white cisgender males from the middle class. However, with the rise of 5th wave emo, and the subsequent largest influx of people other than the aforementioned historical majority, revolutionary ideologies seem to be making a comeback.

The frontwoman of acclaimed 5th wave band Home is Where can be seen in pictures proudly displaying a hammer and sickle on her T-shirt, with lyrics further cementing her more radical political positions. As opposed to the strictly verbal castration of the GOP advocated by Jake Ewald in the lyrics of Voting Early, throughout I Became Birds, Brandon Macdonald discusses actions much more in line with radical political beliefs such as assassinating the president and lighting policemen on fire.

While it is impossible to say exactly where this newfound interest in revolution originates, it likely stems from the genre’s ongoing demographic shift to be inclusive of more oppressed people, in tandem with recent trends in US politics, particularly the increased persecution of trans individuals.

Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla, a band I play in that just put out our debut EP Standing Here Like The band is made up of leftists and the aforementioned effects of alienation from labor were central in creating the lyrics and emotional feeling of the songs we wrote for it.

As emo grows and changes I hope that these connections between the emotional alienation so prevalent in the genre’s history and class consciousness will move closer to the forefront of our discussions around it. While our lyrics in this project do not strive to capture the revolutionary energy of Home is Where’s lyrics (this does not mean we do not sympathize with these ideas), the music that we create is, in the same way, a reaction to the material circumstances that the capitalist mode of production has created.

It’s easy to kick myself for going soft, or abandoning my roots. Even as young as I am, I barely connect with punk a fraction of how deeply I did at 16. But the more I think about the source of this longing that drives me to write twinkly guitar lines and strum Major 9 chords, the more I realize that I’m still doing the same thing I was before, just with a new perspective.

It’s nice to think that these basement emo shows could someday serve as organizing spaces for the vanguard party, but I doubt it. “Tokyo” will never become the anthem of the proletarian state. But as we share with each other our words and songs, those fruits of our labor that the bourgeoisie can’t take from us, then we can, in a way, build forts in the woods again.

We can remind ourselves that it doesn’t have to be like this. We are Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla. We are communists.”